The Treaty of Brétigny (1360): Peace That Didn’t Last

- Davit Grigoryan

- Aug 13, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

By the mid-14th century, England and France were both deeply exhausted. The Hundred Years’ War, which began in 1337 over King Edward III’s dynastic claim to the French throne and disputes over territory, had dragged into a grueling stalemate. The English, though fewer in number, achieved stunning victories through discipline and the deadly power of the longbow. Their triumph at Crécy (1346) had already exposed the vulnerability of French chivalry. But a true disaster for France struck a decade later, in the Battle of Poitiers (1356).

There, the small English force led by the Black Prince, son of Edward III, once again crushed a far larger French army. The defeat reached its dramatic climax with the capture of King John II of France, known as John the Good. The loss of the monarch—a figure of almost sacred significance—plunged France into political chaos. Already exhausted by years of war, the kingdom was left without a central authority, triggering peasant uprisings (the Jacquerie) and a fierce struggle for the regency.

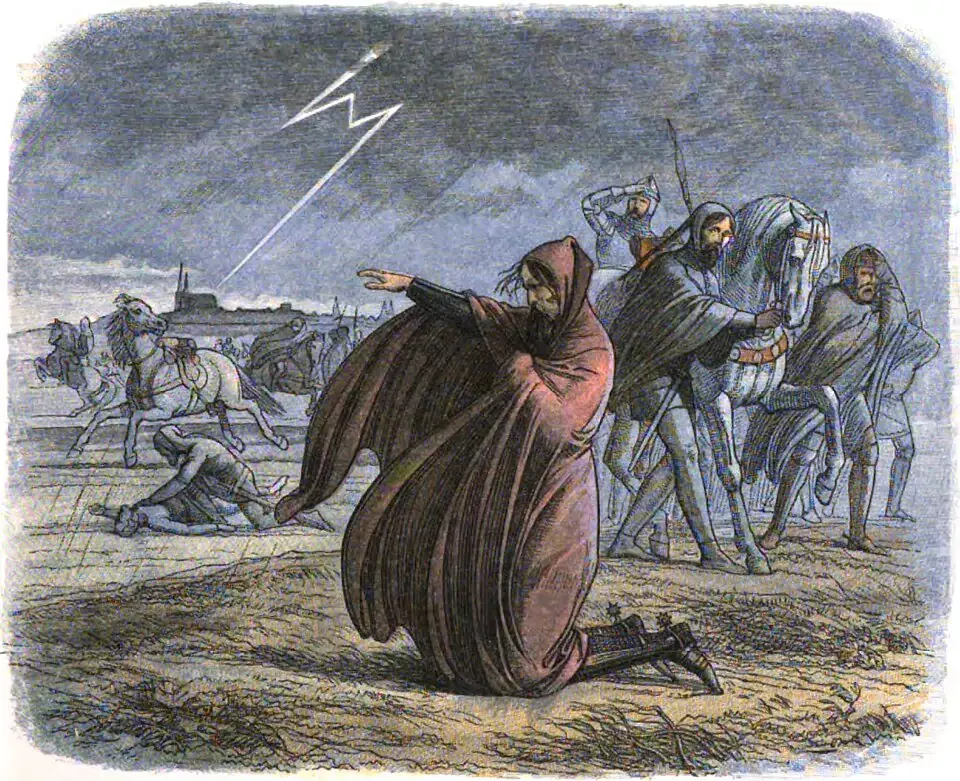

Yet England, despite its victories, was also drained. Waging war on the continent demanded enormous resources, placing a heavy burden on both the treasury and the population. But the most devastating, almost apocalyptic blow to both sides came not from the battlefield, but from the Black Death. The bubonic plague, which swept through Europe between 1347 and 1351, wiped out up to a third—and in some regions, nearly half—of the population. It was a demographic and economic disaster of unprecedented scale: there were too few people left to work the fields, pay taxes, or fight. Trade ground to a halt, and villages stood abandoned.

It was this combination of factors—the military dominance of England, symbolized by the capture of King John II, the deep political instability in France, and the all-consuming economic and demographic exhaustion from the war, worsened by the Black Death—that created the fragile ground on which the Treaty of Brétigny became possible for the first time in decades. Both crowns were desperate for a pause, a chance to catch their breath and restore some semblance of order to their battered kingdoms. At the heart of this weary stalemate stood the French king himself, whose release would become a central issue in the negotiations to come.

Negotiations and Terms of the Treaty of Brétigny

The negotiations aimed at halting the bloody carousel of the Hundred Years’ War were long and arduous, reflecting the depth of mutual distrust. They began as early as 1358, when France—ruled in the absence of its captive king by the young Dauphin Charles (the future Charles V the Wise)—stood on the brink of collapse. The main burden of talks fell on the English envoys, led by the Earl of Salisbury, and the French delegation, headed by the Archbishop of Sens. Initial meetings in London and Paris reached a deadlock, but a decisive breakthrough came in the small village of Brétigny near Chartres in the spring of 1360. It was there that a draft agreement was reached, later finalized and ratified in October of the same year at Calais.

The terms of the Treaty of Brétigny seemed like a stunning triumph for Edward III. The English king, who had fought for decades for the French crown, agreed—formally and temporarily—to renounce his claim to the throne of France. This concession, however, came at a lavish price. In return, Edward received vast territories in southwestern France in full sovereignty, free from any feudal obligations to Paris. Under the English crown fell not only traditional Gascony but also extensive lands: Aquitaine (which became the core of his holdings), Poitou, Limousin, Périgord, Calais with its surrounding area, and part of Ponthieu. In effect, a third of France came under London’s direct control, providing a powerful base for future influence. Of particular value were the rich wine-producing regions around Bordeaux.

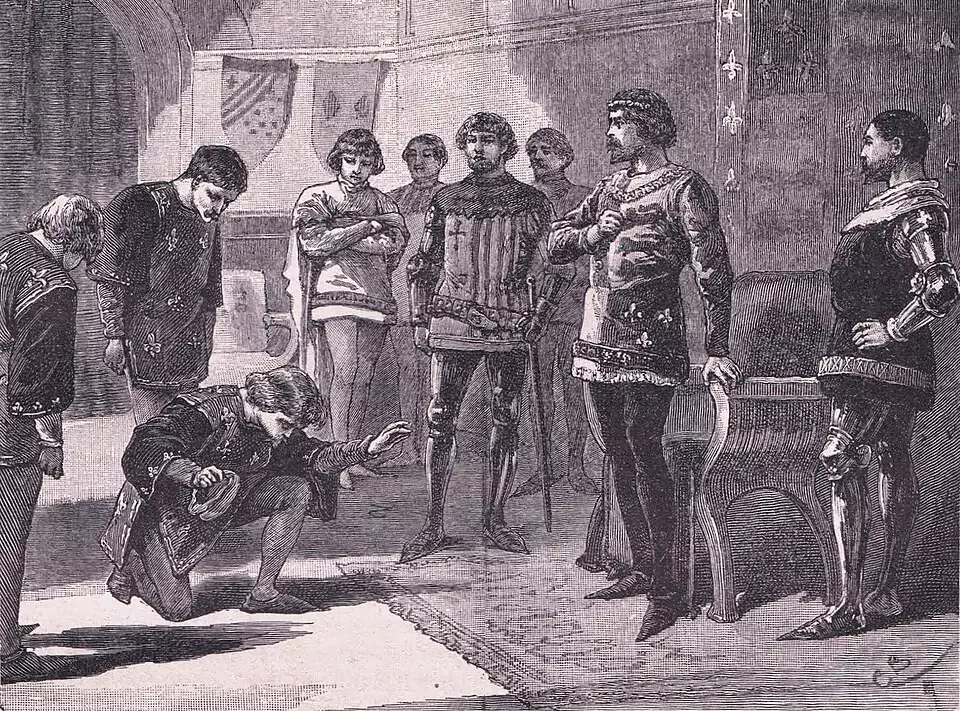

The second pillar of the treaty was the release of King John II. The price for his freedom was astronomical—a ransom of three million gold écus, the equivalent of several years’ worth of the kingdom’s entire budget. To guarantee payment of the first installment and ensure compliance with the territorial concessions, France was required to hand over forty noble hostages to England, including two of the king’s sons. One of them—the young Prince John—was left in England as a pledge of good faith, where he would later die.

At the time, the Treaty of Brétigny was seen as a triumph of English diplomacy and military power. Edward III had secured the maximum expansion of his continental holdings, gaining them under unprecedented terms of full independence. France, on the other hand, appeared to have bought a respite and the freedom of its king at the cost of humiliating territorial losses and an unbearable ransom payment. A peace built on such an imbalance inevitably carries within it the seeds of its destruction.

Immediate Impact and Reactions

The ratification of the Treaty of Brétigny sparked a wave of contrasting emotions on both sides of the English Channel. In England, it was greeted as a triumph. London rejoiced, believing Edward III had achieved the impossible—vast lands free from vassalage and a staggering ransom for King John II. The king was hailed as the greatest monarch since Richard the Lionheart. Merchants, especially from port cities like Bristol and Southampton, eagerly anticipated a boom in trade with the new territories. Bordeaux wine and salt from Poitou now flowed into England duty-free and without the threat of piracy. The war-drained treasury began to fill with the first installments of the ransom, allowing for some tax reductions.

However, behind the facade of widespread celebration, anxiety lingered. Many English knights and mercenaries, who had lived off the spoils of war for years, suddenly found themselves without work. Their discontent grew—peace had taken away their primary source of income and loot. Moreover, governing the vast new territories required resources and the loyalty of the local population, which was far from guaranteed.

In France, the reaction was much darker. Although King John II’s return to Paris in December 1360 was marked by official celebrations—a significant display of legitimacy and hope for stability—the joy was bitter. The terms of the treaty were seen as a national humiliation. The loss of vast territories (Aquitaine, Gascony, Poitou) struck a heavy blow to the prestige of the crown and the economy. The astronomical ransom of three million écus placed an unbearable burden on an already devastated population. To raise the funds, extraordinary taxes were imposed—such as the infamous gabelle, the salt tax—which sparked unrest and resistance. The nobility, whose lands had fallen under English control, were furious. Many were forced to swear allegiance to Edward III or risk losing their estates, an act widely viewed as betrayal.

The treaty’s immediate impact was also felt in the economy. For several years, a respite from the Hundred Years’ War took hold. Roads became safer, fairs were revived, and trade between regions—especially in the southern provinces now united under English rule—flourished. For example, the port of Bordeaux experienced a brief boom. However, this peace was fragile and bought at a high price. While central authorities struggled to enforce the treaty’s terms, bands of unruly mercenaries known as the “Free Companies” roamed the war and plague-ravaged regions. They pillaged villages and towns, spreading chaos and undermining the very idea of peaceful order. Their lawlessness was a grim omen, revealing that true pacification had not been achieved. The peace of 1360 was not the end of the conflict, but rather a deep, uneasy breath before the next storm. The king’s return did not heal France’s wounds; it merely covered them with an expensive bandage.

Why the Peace Failed

The Treaty of Brétigny, which had promised long-awaited peace, began to unravel almost immediately after its ratification. Its collapse was not sudden—it was the result of deep, systemic flaws within the agreement itself and the harsh realities of the postwar period.

The main problem was the impracticality of the territorial terms. The treaty required France to fully and permanently cede the specified lands—Aquitaine, Gascony, Poitou, and others—to England, including cities, castles, and the loyalty of the local nobility. In reality, however, the “transfer” process descended into chaos. Many French lords refused to swear allegiance to Edward III, viewing it as a betrayal of the crown. Paris sabotaged the withdrawal of garrisons, and the local population—especially in Poitou—openly resisted the change of overlordship. Watching these delays, Edward III quickly grew frustrated: by 1364, a significant portion of the territories remained de facto under French influence. A legal loophole in the treaty—the lack of a clear mechanism for the transfer—became a breach through which mutual distrust poured in.

France’s financial collapse dealt the final blow to the fragile peace. The ransom for King John II—three million écus—proved unbearable. Despite harsh taxes, including the salt gabelle and levies on cities, by 1363 only half the sum had been raised. In despair, King John made a fateful decision: in 1364, he voluntarily returned to English captivity, unable to secure the payments or the release of the hostages (his son, Louis of Anjou, had fled from London, breaking his word). The king’s death in captivity that same year buried the spirit of the treaty for good.

At the same time, economic hardships fueled a social explosion. The heavy tax burden, worsened by the aftermath of the Black Death, sparked waves of uprisings across France. But the greatest plague was the Free Companies—bands of demobilized mercenaries from both sides. Stripped of their wartime income, they terrorized villages, blocked roads, and even seized towns like Pont-Saint-Esprit in Provence. Neither England nor France had control over them, and their lawlessness made any post-treaty stability a mere illusion. The peace did not bring security—it brought anarchy.

The climax came with the rise to power of Charles V the Wise in 1364. The new king of France, who had served as regent, saw the treaty as a humiliation. He skillfully used England’s failure to fulfill its obligations—formally, Edward III was supposed to renounce his claim to the French crown only after the full transfer of lands, which never happened—as a pretext. Systematically strengthening the army, administration, and alliances, Charles V methodically pushed the English out of contested enclaves. By 1369, after the Gascon nobility appealed to Paris against the tax policies of the English governor (the Black Prince), France declared war renewed. The Treaty of Brétigny, which had lasted only nine years, collapsed under the weight of unresolved contradictions, leaving behind nothing but bitter resentment and the causes for an even more brutal continuation of the war.

Legacy of the Treaty of Brétigny

The Treaty of Brétigny left behind not peace, but a deep—though bitter—mark on the body of the Hundred Years’ War. Its main legacy was not resolution, but a vivid demonstration of the complexities medieval diplomacy faced in resolving fundamental conflicts. The nine years of formal truce (1360–1369) were not an ending, but merely an interlude that shifted the dynamics of the struggle.

First and foremost, the treaty gave France a priceless respite, which Charles V the Wise used with exceptional foresight. Rather than wasting this time, he focused on fundamental reforms: reorganizing the army (reducing the role of knightly cavalry, developing artillery, and adopting a scorched-earth tactic), strengthening royal authority, restoring financial order, and combating the Free Companies (partly redirecting them to Spain). These measures transformed France from a nearly defeated foe into a formidable power capable of waging a war of attrition. England, on the other hand, lost the initiative. Managing vast but fragmented territories—especially Aquitaine—proved difficult and costly. The harsh tax policies imposed by the Black Prince in Bordeaux alienated the local nobility, who increasingly turned their loyalties toward Paris.

The collapse of the Brétigny peace acted as a catalyst for a new, harsher phase of the war. When hostilities resumed in 1369, it was no longer a series of chivalric clashes. Under the leadership of talented commanders like Bertrand du Guesclin, France avoided pitched battles, instead relying on guerrilla tactics, sieges, and the systematic expulsion of the English from their enclaves. The defeat of the English fleet at La Rochelle in 1372 by Charles V symbolized this turning point: it not only ended English naval dominance and severed vital supply lines to Aquitaine but also paved the way for a swift reconquest of French lands. By the end of the 14th century, England retained only a narrow strip of territory around Calais and Bordeaux—a mere shadow of the Brétigny conquests.

The treaty also became an important legal and diplomatic precedent. Its detailed but poorly conceived structure—especially the conditional nature of Edward III’s renunciation of the French crown and the unclear mechanism for transferring lands—highlighted the dangers of ambiguity in international agreements. Later peace efforts, including those during subsequent phases of the war, took this bitter lesson to heart, striving for greater clarity and enforceable guarantees, though not always successfully.

The historical significance of Brétigny lies in its tragic illustration: it proved that a peace imposed by force and humiliation is unsustainable. Even the most favorable terms on paper collapse if the defeated side refuses to accept their loss and the victor overestimates their ability to govern. The 1360 treaty did not end the Hundred Years’ War; it merely shifted it into a darker phase, where the hope for chivalric glory gave way to the harsh reality of total conflict. Its brief respite was not the end of suffering but just a pause before decades more of bloodshed and destruction.

Comments