Edward the Black Prince: The Legendary Warrior of the Hundred Years’ War

- Davit Grigoryan

- Aug 18, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

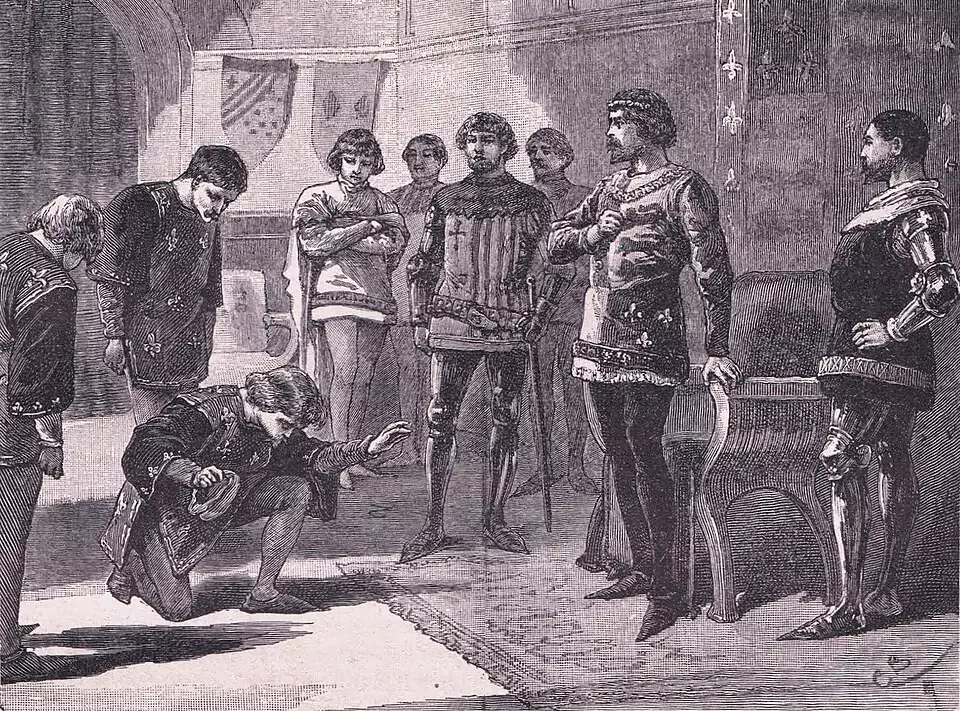

When it comes to the legendary figures of the Hundred Years’ War, the name of Edward the Black Prince inevitably comes to mind. As the eldest son of the powerful King Edward III of England, he was not only born into royalty but also forged in the furnace of one of the longest and bloodiest conflicts of the Middle Ages. His life, shrouded in an aura of knightly valor and military genius, became a symbol of English strength and ambition during that era.

Even his contemporaries saw him not merely as a prince but as a true warrior whose victories on battlefields like Crécy and Poitiers instilled fear in his enemies and pride in the hearts of his countrymen. Edward the Black Prince entered history not only as the heir to the throne—though he never became king—but above all as a brilliant commander whose tactics and personal bravery turned the tide of the conflict in England’s favor.

His legendary nickname, the armor displayed in Canterbury Cathedral, and the very memory of his feats continue to captivate the imagination today. They draw us back repeatedly to the pages of the Hundred Years’ War to grasp the magnitude of this extraordinary figure. Studying the history of the Black Prince is key to understanding an entire era.

Early Life and Background

The birth of Edward the Black Prince in June 1330 at Woodstock Palace was an event of immense significance for the English crown. He was the long-awaited firstborn of the young and ambitious King Edward III and his wife, Philippa of Hainault. His very name, inherited from his father, spoke of the great hopes placed upon him—he embodied dynastic continuity and was the future guarantor of the Plantagenet power. The Black Prince’s childhood unfolded in an atmosphere of royal grandeur and strict upbringing, typical of medieval English princes.

From an early age, young Edward was immersed in a world where concepts like honor, duty, and knightly valor were not mere abstractions but the foundation of existence. His education extended far beyond literacy and Latin. Under the guidance of experienced tutors such as Sir Walter Burley, he mastered the arts of horsemanship, swordsmanship, lance skills, and battle tactics—everything required of a future military leader. His father’s court was a center for the revival of the chivalric ideal, inspired by the legends of King Arthur. The boy absorbed these values, watching tournaments and ceremonies, and listening to stories of heroic deeds.

At just seven years old, Edward was nominally granted the title of Earl of Chester, and by thirteen, he was solemnly knighted by his father on the eve of a pivotal campaign. This was far more than a mere formality. The knighting of the young prince at such a tender age, just before going to war, was a powerful symbol: the heir to the throne was expected to share the hardships and risks of battle alongside his subjects.

In 1346, at the age of sixteen, he stepped onto the battlefield for the first time at Crécy. The early years Edward the Black Prince spent amidst the luxury of Windsor sharply contrasted with the harsh realities of the war he entered so young. This experience became his primary school of life. Observing his father as a commander, participating in councils—at first only as an observer—enduring the hardships of campaign life, and feeling the weight of responsibility for the soldiers under his command, the young prince was forged.

His character, nurtured by the ideals of chivalry and honed through campaigns, shaped the leader whose name would soon strike fear across France. Childhood ended early; the legend, tempered in the steel of an early military career, was just beginning.

Military Career and Key Battles

Edward the Black Prince’s military career unfolded rapidly and brilliantly, becoming a textbook example of medieval command talent. His path to glory began at just sixteen on the battlefield of Crécy in 1346. Although the formal commander of the English forces was his father, King Edward III, the young prince was given command of a crucial flank. Legend has it that when his position wavered under the fierce attacks of French knights, the king refused to send reinforcements, wanting his son to “earn his spurs” on his own. Edward held his ground.

This victory, owed largely to the discipline of the English longbowmen and the skillful deployment of forces, became a harsh but invaluable lesson and the heir’s first triumph. Here, he learned key principles that he would later apply masterfully: the effective combination of troop types (longbowmen and dismounted knights), the use of defensive positioning, and the careful timing of counterattacks.

However, the true masterpiece of Edward’s military genius came ten years later at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. Leading a raid into French territory, the prince found himself trapped: a numerically superior French army commanded by King John II the Good cut off his path of retreat. The situation seemed hopeless.

But Edward, demonstrating cool-headedness and strategic brilliance, chose the perfect defensive position atop a hill protected by natural barriers. He repeated the success of Crécy, but this time he perfected the tactics. His longbowmen unleashed a deadly volley on the charging French cavalry, followed by a devastating counterattack from dismounted English and Gascon knights.

The result was staggering: the French army was crushed, and King John II himself was taken prisoner. This victory brought Edward unprecedented fame and wealth, and England secured vast territorial concessions in the Treaty of Brétigny. It was after Poitiers that he became the Prince of Aquitaine, gaining control over extensive lands in southwestern France.

There is no consensus about the origin of his famous nickname, “The Black Prince.” It was not widely used during his lifetime. The name may be linked to the color of his armor or heraldry—though his shield was a dark blue adorned with golden lilies—or perhaps to his harsh reputation following events like the brutal massacre at Limoges in 1370, when thousands of townspeople were slaughtered on his orders as revenge for a rebellion. This cruelty, contrasting sharply with the image of the ideal knight, adds dark shades to his legend.

His rule in Aquitaine, despite the initial splendor of his court in Bordeaux, was complicated by heavy taxation and growing discontent among the local nobility, which eventually contributed to the resumption of war. Even his last major campaign—a victorious expedition in 1367 to Castile (Spain) to restore his ally Pedro the Cruel to the throne, culminating in the Battle of Nájera—though a military triumph, turned into a financial disaster, undermining his health and the resources of Aquitaine.

His military career, dazzling in its victories, also carried the seeds of future troubles.

Personal Life and Legacy

Behind the formidable figure of the military commander stood a man with a complex fate and personal drama. Edward the Black Prince’s family became the center of his world beyond the battlefield. His marriage to Joan of Kent in 1361 was not merely a dynastic alliance but also a union of love—albeit one clouded by scandal.

Joan, twice widowed and carrying a controversial reputation—known as the “Fair Maid of Kent,” whose beauty was legendary—drew disapproval from the Pope and even some coldness from King Edward III due to the complicated history of her previous marriages. Nevertheless, the prince showed determination and secured the church’s permission. Despite all the gossip, their marriage proved to be both happy and enduring.

Joan accompanied her husband to Aquitaine, where their court in Bordeaux was renowned for its splendor and chivalric spirit.

Their children were a source of both joy and sorrow. Two sons, Edward and Richard, born in Angoulême, became the hopes of the dynasty. However, the elder son, Edward, died at the age of six in 1371. This loss was a heavy blow to the parents. The younger son, Richard, born in 1367, remained their sole heir.

It was Richard who, after the deaths of the Black Prince and King Edward III, ascended the throne as King Richard II in 1377, at only ten years old. The Black Prince’s death in June 1376, a year before his father’s, was a moment of great significance and was perceived as a national tragedy.

Weakened by years of military campaigns, the harsh climate of Aquitaine, and likely chronic dysentery or another debilitating illness (some sources suggest tuberculosis or complications from battle wounds), his health steadily declined after returning from Spain in 1371. He died at the age of 45, never having become king—a grim irony for a man whose life was devoted to serving the crown.

The legacy of Edward the Black Prince proved to be profound and multifaceted. He became the archetype of the medieval knight-prince: a courageous warrior, a generous patron, and a model—though not without flaws—of chivalry. His famous armor and helmet, suspended above his magnificent bronze funerary effigy in Canterbury Cathedral, serve as an eternal reminder of his glory.

His court in Bordeaux was a cultural center, and his membership in the Order of the Garter symbolized the ideals of knighthood. Contemporary figures like Chaucer mentioned him with respect in The Canterbury Tales. Yet historians offer a more nuanced assessment of his character. An undeniable military genius and hero of Crécy and Poitiers, he was also a ruthless conqueror—exemplified by the massacre at Limoges—and his governance of Aquitaine, which sparked uprisings, revealed limitations as an administrator.

His death left England without a strong adult heir, indirectly contributing to the instability that would mark Richard II’s reign. But as a symbol of martial valor and the chivalric spirit at the height of medieval England, the legend of the Black Prince has endured through the centuries, overshadowing many contradictions of his real life.

Why Edward the Black Prince Matters Today

Edward the Black Prince has long passed into history, yet his figure has not been lost on the dusty pages of chronicles. His significance for the present stems from several key aspects that make him more than just a fortunate commander of the distant past.

First and foremost, he remains a central figure in understanding the very phenomenon of the Hundred Years’ War—a protracted conflict that shaped the national identities of both England and France. His triumphs at Crécy and especially at Poitiers became symbols of English military supremacy in that era, examples of tactical genius still studied by military historians today.

His ability to use terrain effectively and to combine longbowmen with dismounted knights anticipated the future development of military art, demonstrating that discipline and strategy could overcome numerical superiority and traditional knightly bravery.

Secondly, the Black Prince embodies the complex ideal of medieval knighthood. He was simultaneously a celebrated warrior, a patron of the arts—his court in Bordeaux was magnificent—and a figure whose reputation was shadowed by cruelty, as in the case of Limoges. This contrast makes him more human and relevant to us today. He reminds us that heroes of the past were not flawless icons but living people with their virtues, ambitions, and flaws.

His cultural legacy is palpable: from his majestic funerary effigy in Canterbury Cathedral—one of the masterpieces of medieval art and a pilgrimage site for tourists and historians alike—to references in classic literature (such as Shakespeare, who focused on Richard II) and modern historical novels, films, and even video games, where his image is often romanticized as the archetypal medieval hero.

Finally, his legacy is closely tied to the fate of the English monarchy. His premature death and the ascension of the underage Richard II marked a turning point that indirectly led to dynastic crises—including the overthrow of Richard II—and ultimately to the Wars of the Roses. This invites reflection on the fragility of power and the long-term consequences of the decisions and destinies of individual people.

Edward the Black Prince remains important today not only as a brilliant tactician or a symbol of the chivalric era but also as a figure whose life and posthumous legend prompt us to think about the nature of leadership, the cost of glory, the complexity of historical judgment, and how myth and reality intertwine to shape our understanding of the past. His story is not just a tale of battles; it is part of a cultural code reminding us of the rises and falls inherent in human history itself.

Comments