Battle of Poitiers (1356): The Black Prince’s Greatest Victory

- Davit Grigoryan

- Aug 11, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

Imagine a golden September day in 1356, somewhere in the heart of France, not far from the ancient city of Poitiers. The air is filled with an uneasy hum—not the buzzing of bees, but the neighing of thousands of horses and the clash of weapons. On September 19, these hills became the stage for one of the most dramatic and unexpected episodes of the Hundred Years’ War—the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. This clash, the culmination of a daring English raid, forever entered the annals of military history—not so much for its scale, but for its staggering consequences and the way it vividly exposed the crisis of medieval chivalry.

At the heart of the events stood two key figures of the era. On one side was the young yet already renowned Edward the Black Prince, son of England’s King Edward III. He commanded a relatively small but well-organized army, hardened by previous campaigns. His goal was simple and devastating for France: to plunder, burn, expose the weakness of the French crown, and lure the enemy into open battle. Marching toward him was none other than King John II of France, called “the Good,” at the head of a massive, glittering force of knights, outnumbering the English several times over. The French were utterly confident of an easy victory—they had finally caught up with the audacious prince and were determined to wipe his force from the face of the earth, avenging past humiliations such as the Battle of Crécy.

Yet the Battle of Poitiers delivered a crushing surprise. It was not merely another skirmish in the Hundred Years’ War, but a true turning point. Defying all expectations and the logic of numerical superiority, the day ended in a devastating defeat for the French. But an even greater shock awaited Europe: King John II of France himself was taken prisoner. The capture of a reigning monarch on the battlefield was an unprecedented event—a genuine political catastrophe for France. The consequences of that September clash were profound: it shook the very foundations of the French state, brought England immense prestige and enormous spoils, and, most importantly, set the course of the grueling Anglo-French conflict for decades to come. How could such a thing happen? The answer lies in the events that preceded that bloody day at Poitiers.

Background: The Road to Poitiers

To understand why the armies clashed at the walls of Poitiers in that fateful September of 1356, we must look back a decade. By then, the Hundred Years’ War had already raged for nearly twenty years, and France had yet to recover from the harsh lesson dealt at Crécy in 1346. There, English longbowmen and disciplined infantry utterly crushed the vastly superior French chivalry. The long and grueling siege of Calais that followed only deepened the humiliation of the French crown and drained its resources. It seemed that fortune had turned away from the lilies for good.

But war is not only about great battles. Having secured their hold on Guyenne and Calais, the English adopted the exhausting tactic of the chevauchée—devastating raids deep into French territory. These raids had several purposes: to undermine the enemy’s economy, to demonstrate his inability to protect his subjects, and, most importantly, to provoke the French king into a pitched battle on terms favorable to the English. It was with just such a mission that, in the summer of 1356, Edward, the Black Prince—already famed as a bold and gifted commander—set out from Bordeaux at the head of a relatively small but highly mobile army of seasoned veterans.

His route ran through the rich lands of Gascony, Languedoc, and Auvergne, before turning north into the very heart of France—the Poitou region. This choice was no accident. Poitou was not only a fertile breadbasket, but also a strategically vital area linking the English holdings in the southwest with their allies in Brittany and Normandy. Devastating Poitou struck at the prestige of the king and his vassals with particular force. Towns and villages burned, fields were trampled, and the population fled or perished. The Black Prince advanced methodically, cutting through the kingdom like a red-hot blade through flesh.

At that time, the French throne was held by John II, called “John the Good.” His nickname reflected knightly ideals more than political insight. The humiliations at Crécy and Calais, the boldness of the English raids—especially the daring campaign led by the enemy king’s son—all demanded a response. The king thirsted for revenge, eager to wash away the gloss of the English prince’s reputation with the blood of his soldiers. He saw the Black Prince not so much as a dangerous foe but as an arrogant youth who needed to be punished. Upon hearing news of Edward’s marauding campaign, John II began assembling a massive army, drawing knightly contingents from every corner of the kingdom. His goal was not merely to stop the raid but to surround and annihilate the English force and capture the prince himself. It seemed that numerical superiority and chivalrous valor guaranteed success. The French were certain that this time would be different from the Battle of Crécy. They were eager for battle, unaware that the road to Poitiers was leading them straight into a new catastrophe, born of a chain of political ambitions and military miscalculations.

The Armies and Strategies

When the two armies finally met near Poitiers on the early morning of September 19, the contrast between them was striking, even to the least discerning observer.

King John II’s French army was the embodiment of the classic medieval knightly ideal—a majestic and formidable sight. Historians estimate its size at around 15,000 to 16,000 men, although, as is often the case, the exact numbers remain disputed. The main striking force consisted of heavily armored knights and men-at-arms—the elite of the French nobility—clad in solid armor and mounted on powerful warhorses.

They were supported by hired Genoese crossbowmen, whose effectiveness, however, was severely limited after previous defeats, and a fairly large but poorly organized infantry drawn from urban militias. The French advantage was overwhelming—at least three to one.

Fueled by confidence, a thirst for revenge after the Battle of Crécy, and numerical superiority, the French arrogance was off the charts. King John, surrounded by a brilliant retinue of dukes and counts, envisioned victory as a simple, straightforward action: a powerful, crushing cavalry charge designed to smash the English in the very first attack like a clay pot.

The difficulty of commanding such a diverse mass of aristocrats—each eager for personal glory and ready to challenge orders—was underestimated. Discipline, sadly, was not a strong point of this magnificent force.

Edward, the Black Prince’s army was of a different kind—far smaller in number, around 6,000 to 7,000 men, and lacking in outward splendor, yet honed to a razor’s edge. Its core was made up of veterans, hardened by campaigns and masters of their craft. The true strength of the English did not lie in their knights, but in their famed English and Welsh archers. Often dressed in practical quilted jackets or light mail, and armed with deadly longbows, these men had been the key to every previous victory. Their rate of fire and range were unmatched by crossbows.

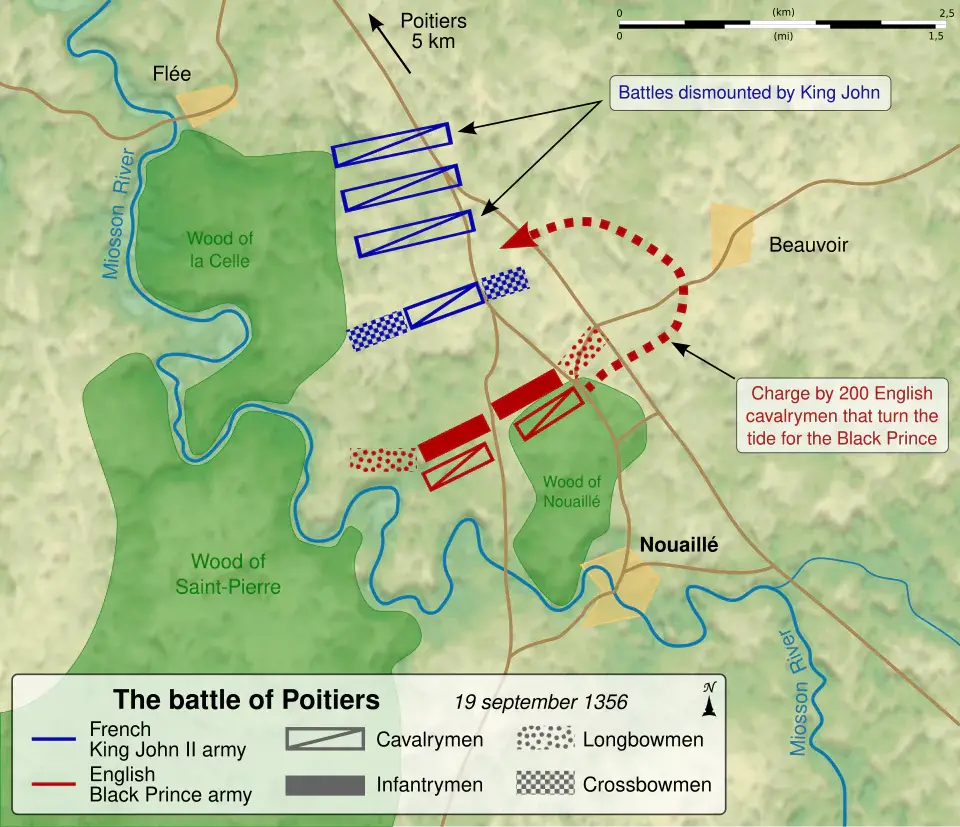

The Black Prince’s tactics were defensive and methodical, perfected through experience. He carefully chose a position on a hillside, shielded by natural obstacles—vineyards, hedges, and a stream to the front, and dense woodland on the flanks. This narrowed the attack front, depriving the French of the ability to fully exploit their numerical superiority. The archers were placed on the flanks and, possibly, in forward wedges so their lethal fire could strike the attackers at an angle.

Knights and dismounted men-at-arms held the center, ready to meet the assault in a tight formation. Discipline and precise execution of orders were upheld to the highest degree. The Prince and his commanders—such as the seasoned Earl of Salisbury and the captain Jean de Grailly—understood that their only chance lay in withstanding the first and most ferocious onslaught, wearing the enemy down, and only then counterattacking. They relied on patience, discipline, the skill of their archers, and the advantages of the terrain.

While the French prepared for a large-scale knightly tournament, the English were building a deadly trap. Which approach would prove victorious would soon be revealed on the day of battle.

The Course of the Battle of Poitiers

The morning of September 19, 1356, began for both armies with tense anticipation. The French, confident of a swift victory, formed up for the attack—but their vast host wasted precious time in disputes over honor and position in the ranks, the classic problem of a feudal levy.

It was only by midday, under the blazing sun, that the first French division, commanded by Marshals Audrehem and Clermont, finally advanced. These were dismounted knights and infantry tasked with breaking a gap in the English defenses. Yet their route led them through vineyards and hedgerows—the very natural obstacles the Black Prince had so skillfully chosen to exploit. The formation was already disrupted before they even reached the enemy.

And then came the most dreadful part for the attackers.

The English and Welsh archers, concealed on the flanks and ahead of the main force, unleashed a deadly storm of arrows. The air hissed and whistled as the volleys flew. The longbows struck far and fast, their steel-tipped shafts finding the weak points in armor, felling horses, and sowing panic in the tightly packed ranks of the advancing French.

The first French wave, suffering grievous losses and thrown into complete disorder, fell back in confusion, colliding with the ranks of the next division. A brief, ominous pause followed.

The second attack, led by the young Dauphin Charles (the future Charles V “the Wise”) and the Duke of Orléans, was more organized and determined. French knights and infantry managed to push back part of the English archers and hack their way into the ranks of the dismounted men-at-arms in the center.

A fierce hand-to-hand struggle erupted. The clash of swords, the splintering of lances, the cries of the wounded—the field near Poitiers became a hellish cauldron. Pressed by superior numbers, the English began to slowly fall back up the slope.

At the English command post, a sense of impending disaster took hold. According to legend, Edward, the Black Prince, threw himself into the thick of the fighting to rally his men. It seemed the scales of battle were about to tip in France’s favor.

It was at this critical moment, when the outcome hung by a thread, that King John II—impatient and eager for personal glory—threw his reserve into the fray: the very flower of French chivalry, including his young son Philip. This was the third and most powerful, most dangerous assault.

Under the royal banner, the French knights closed ranks and crashed into the exhausted English. The onslaught was ferocious. Yet here, the training, discipline, and composure of the English came into play. They managed to hold their formation.

What’s more, the commander of the Black Prince’s reserve, Captain Jean de Grailly, executed a brilliant maneuver. A small but mobile force of Gascon knights, hidden in the woods, suddenly struck at the flank and rear of the king’s entourage. This blow, like a dagger in the back, spread panic among the French already bogged down in their frontal assault. Their formation collapsed completely.

A disorderly rout began. But the main drama unfolded around King John II. He, his son Philip, and his closest companions found themselves encircled by the English. The king fought with desperate bravery—his sword broke, yet he continued the struggle with a battle axe.

The odds, however, were overwhelming. After a fierce fight in which many of his defenders were killed or wounded, King John II of France—called “the Good”—was taken prisoner. The news spread instantly across the field, breaking the spirit of the French army entirely.

The Battle of Poitiers turned into a rout. The surviving knights and infantry fled in panic, pursued by English cavalry detachments. By evening, the battlefield belonged to Edward, the Black Prince, who had won his greatest and most improbable victory. The price was high, but the outcome—the capture of the French king—was a sensation that shocked all of Europe and forever altered the course of the war.

Aftermath and Legacy

The immediate aftermath of the Battle of Poitiers struck France like a thunderclap. The capture of King John II—a figure not only of military but also of almost sacred significance—plunged the country into chaos.

A state already weakened by war, plague, and economic crisis now found itself without central authority. Power passed to the young Dauphin Charles, the future Charles V “the Wise,” but his authority was fragile. Paris erupted in the uprising of Étienne Marcel, the provinces seethed with peasant revolts (the Jacquerie), and the great noble houses, freed from the restraining hand of the king, pursued their private wars.

France had sunk into a profound political and social crisis—one that verged on complete disintegration.

For Edward, the Black Prince, and for England, the victory was an unprecedented triumph and a source of immense profit. The most valuable prize—the King of France—became the key to an enormous ransom.

Negotiations over his release dragged on for years and culminated in the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. This agreement marked the high point of English success in the Hundred Years’ War. Edward III formally renounced his claim to the French crown, but in exchange, he received full sovereignty over vast territories: Gascony, Guyenne, Poitou, Calais, and Ponthieu—nearly a third of modern France.

The ransom for John II was set at the staggering sum of three million gold écus, the equivalent of several years’ worth of the kingdom’s budget. It seemed that England had achieved everything it could desire.

Yet the long-term consequences of Poitiers proved far more complex and ambiguous. The Treaty of Brétigny brought only a temporary lull. The enormous ransom placed a crushing burden on the French economy, while the loss of territory left a deep scar on the nation’s consciousness.

When John II returned to France (with part of the ransom still unpaid) and died in 1364, the throne passed to the determined Charles V, making a quest for revenge inevitable. The new king launched sweeping military reforms, prioritizing a professional army, artillery, and a cautious strategy that avoided large-scale pitched battles.

By the 1370s, much of the land lost after Poitiers had been recaptured. Thus, while the Battle of Poitiers stood as the most brilliant display of the Black Prince’s tactical genius and brought England temporary gains and unmatched prestige, it did not secure a final victory in the war. On the contrary, France’s humiliation became the bitter seed from which its future unity and resistance would grow.

The military significance of Poitiers is difficult to overstate. The battle was, after the Battle of Crécy, another crushing demonstration of the crisis facing medieval chivalry and the effectiveness of a new model of warfare: disciplined infantry supported by masses of archers, using terrain and defensive tactics to withstand the superior numbers of heavy cavalry.

It proved that the outcome of a battle depends not solely on numbers or individual valor, but on training, discipline, command skill, and the ability to exploit the landscape. The capture of a king on the battlefield was a singular event—a shock to the medieval world—that revealed the fragility of royal authority in the face of military disaster.

The legacy of Poitiers is not only the triumph of the Black Prince but also a grim lesson in the cost of aristocratic overconfidence, and the beginning of France’s long road to national renewal. The battle remains remembered as a symbol of how, on a September day, military fortune and tactical genius could turn the tide of history—yet still fail to break an entire nation’s will to freedom.

Comments