The Rise of Rome: From City-State to Superpower

- Davit Grigoryan

- Aug 25, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

It’s hard to imagine, but the greatest empire of antiquity began its journey as an unremarkable settlement on the banks of the Tiber. In the 8th century BCE, a modest community of farmers and shepherds emerged on seven hills, lost among powerful and highly developed neighbors. The Etruscans, with their impressive art; Greek colonists, bringing ancient philosophy; and the formidable Carthaginians, who controlled the entire western Mediterranean—all looked down on this small town.

Rome seemed to have no chance of achieving greatness. And yet, its meteoric rise is all the more astonishing. How did this small, vulnerable citadel not only survive but eventually dominate the known world, transforming from a humble city-state into a ruling superpower?

The answer lies in a unique combination of strict discipline, a flexible political system, military genius, and an insatiable drive for expansion. Step by step, from its legendary origins to the creation of an imperial machine, these factors shaped the rise of Rome and forever altered the course of world history.

Origins: Rome as a City-State

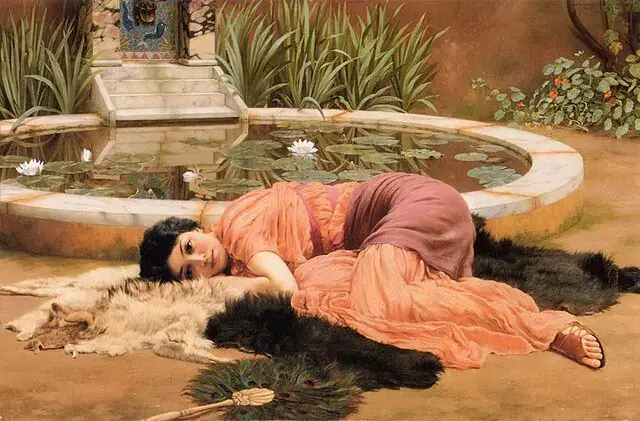

The Eternal City traces its beginnings to legends that, for the Romans, were not mere fairy tales but sacred history—a foundation of their identity. The tale of the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, raised by a she-wolf and said to have founded a settlement on the Palatine Hill in 753 BCE, served as a powerful symbol of divine favor and destiny. Retold countless times, this story instilled in each generation the belief that their small homeland had a special, almost sacred mission.

However, the real history of early Rome was far from poetic. Initially, it was a cluster of rudimentary huts inhabited by Latin and Sabine shepherds, living off subsistence farming and constantly struggling for resources. Their world was governed by the harsh necessity of survival, under the constant threat of hostile tribes and more advanced neighbors.

The main teachers—and at the same time oppressors—of young Rome were the Etruscans. Under their rule, when the Tarquins held power, the city began to take on the characteristics of a true polis. The Etruscans brought Rome advanced engineering technologies for the time: they drained the marshy valley between the hills, creating what would become the Forum; built massive temples dedicated to the Capitoline Triad of gods—Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva; and, most importantly, laid the foundations of state governance by introducing the institution of kingship.

At the same time, Greek culture exerted a powerful influence, arriving through the colonies of Magna Graecia in southern Italy. From the Greeks, the Romans adopted the alphabet, adapting it for Latin, as well as much of their pantheon of gods—merely renaming Zeus as Jupiter and Ares as Mars. This period became one of intense cultural synthesis.

Rome, like a sponge, absorbed the best of the surrounding peoples, yet transformed these borrowings into something uniquely its own. From a simple city-state, enclosed by the formidable walls of Servius Tullius, there gradually emerged a community whose ambitions extended beyond merely defending its fields. It learned to view the world not as a threat, but as a space for future expansion, unconsciously preparing for its extraordinary destiny.

From Kingdom to Republic: Political Evolution

A turning point that forever changed the spirit of Rome came in 509 BCE, shrouded in scandal and tyranny. According to legend, the last Etruscan king, Tarquin the Proud, exhausted the patience of the Roman aristocracy with his despotism and cruelty, and, most notably, through the crime of his son, Sextus, against the virtuous Lucretia. This sparked a popular uprising, the expulsion of the royal family, and a complete rejection of the monarchical system.

This was the official story, but modern historians see a longer and more complex process, in which the aristocratic oligarchy gradually eroded royal power, using any pretext to consolidate its authority. The outcome was the birth of a fundamentally new form of governance—the Republic, or res publica, the “common affair.”

At its heart and mind was the Senate, an assembly of the city’s most respected and noble men, which had evolved from an advisory body under the king into the principal legislative and governing institution. Two consuls, elected annually, directly exercised executive power, each holding equal authority and the right to veto the other, which prevented any one of them from usurping power. This system of checks and balances, in which no magistrate could ever feel completely secure, became one of Rome’s most ingenious innovations.

However, the birth of the Republic did not bring instant justice. On the contrary, it intensified internal conflict, known as the struggle of the orders. Society was split into two camps: the patricii, the hereditary aristocracy that monopolized access to the highest magistracies and the Senate, and the plebs, the disenfranchised majority who bore the full burden of taxes and military service.

The plebeians, aware of their crucial role in the army, used it as their main leverage. They would leave the city in protest (secessio), refusing to defend a Republic that did not belong to them, and demanded written laws to limit the arbitrary power of patrician judges.

The result of this centuries-long struggle was the creation of the Laws of the Twelve Tables in 450 BCE—the first codification of Roman law, engraved on bronze tablets and displayed for all to see. This was a groundbreaking development, as the law, though strict, became public and accessible, rather than a secret kept by patrician priests.

Later, the plebeians gained the right to elect their defenders—the tribunes of the people—whose persons were considered inviolable, and whose word could halt any magistrate’s decision. It was this internal struggle, rather than peaceful development, that forged the Roman political system, making it both flexible and resilient. The constant search for compromise, the integration of elites from conquered peoples, and, most importantly, the principle of the supremacy of law over the will of any single ruler, created a unique social and political structure capable of withstanding the demands of future grand conquests. The Republic learned to govern itself, preparing one day to govern the entire world.

Military Power & Expansion: From Italy to the Mediterranean

Having achieved internal stability, the Republic turned its energy outward, and it was here that its true genius became evident. The conquest of the Italian Peninsula was not a lightning-fast blitzkrieg; it was a centuries-long, methodical, and often ruthless process. The Romans fought against the Samnites in fierce mountain wars, against Gallic tribes whose raids struck terror, and against wealthy Greek city-states in the south, such as Tarentum.

It conflicted with King Pyrrhus of Epirus—who won battles but suffered irreplaceable losses—that the concept of the “Pyrrhic victory” was born: a success equivalent to defeat. Rome, in contrast, could endure setbacks without ever losing its will to fight. Its greatest strength lay not merely in the famed discipline of the legions, but in a unique system for integrating the conquered. Rather than mercilessly plundering subjugated peoples, Rome offered them a complex hierarchy of status—from full Roman citizenship to allied rights. This meant that yesterday’s enemy, once granted a stake in future conquests, could fight in the Roman army tomorrow, making it virtually inexhaustible.

However, the true test of Rome’s strength—and its entry into the ranks of a superpower—came with the Punic Wars against Carthage, a mighty maritime empire that controlled the keys to trade in the Western Mediterranean. These three conflicts, spanning more than a century, were wars of total attrition.

The genius of the Carthaginian general Hannibal, who made the incredible crossing of the Alps and dealt crushing defeats to the Romans at Lake Trasimene and Cannae, brought the Republic to the brink of destruction. Yet the Romans demonstrated their greatest strength: extraordinary resilience and the ability to learn. They abandoned confrontation and adopted a war of attrition, avoiding decisive battles with Hannibal’s army while simultaneously taking the fight to Carthaginian territory in Africa under the leadership of Scipio Africanus.

By emerging victorious in this titanic struggle and wiping Carthage off the map in 146 BCE, Rome secured undisputed dominance. Yet victory brought its first warning signs: unprecedented wealth flooded into the city, corrupting the elite, while the vast new territories demanded a system of governance.

Rome’s response was the creation of provinces and large-scale construction projects—this was the period when the famous roads, straight as arrows and paved with stone, began to be actively built. These arteries allowed legions to move swiftly to any point in the empire and fostered an unprecedented integration of economies and cultures. In this way, military expansion ceased to be an end in itself, transforming instead into a tool for creating a unified world governed from a single center—the Pax Romana—which at that time was still only beginning to take shape in the minds of Rome’s rulers.

From Republic to Empire: Julius Caesar to Augustus

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, the Roman Republic had become a victim of its success. The immense wealth pouring in from the conquered provinces did not strengthen it; instead, it corroded it from within like rust. Traditional values, grounded in the notion of the common good, collapsed under the pressure of relentless greed and the ambition of a narrow layer of the senatorial aristocracy.

Political corruption reached unprecedented levels, and the monstrous gap between a handful of super-rich elites and the masses of impoverished citizens—who had lost their lands due to the influx of cheap slave labor—created intense social tension. Republican institutions, designed to govern a city-state, were utterly unprepared to manage a global power. They stalled, mired in factional quarrels, unable to respond effectively to emerging challenges.

Meanwhile, the army, once composed of citizen militias defending their own homes, gradually became a professional force loyal not to the abstract concept of Rome, but to a particular general who could provide them with loot and land. This shift in the legions’ loyalty proved to be fatal.

Against this backdrop rose the star of Gaius Julius Caesar—a brilliant politician, general, and strategist. He skillfully played on the aspirations of the masses, distributing bread and spectacles, and with his unprecedented popularity among the troops, earned through victories in Gaul, he directly challenged the Senate.

Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BCE with a single legion was more than an act of defiance; it was a demonstration that real power now belonged to whoever controlled loyal soldiers. His dictatorship, marked by sweeping reforms—from the calendar to granting citizenship to provincials—was an attempt to impose order from above. Yet the senatorial aristocracy, seeing him as a usurper, responded with conspiracy and the ritual assassination of the “tyrant” on the Ides of March in 44 BCE. The killers naively believed that by eliminating the man, they would restore the Republic; instead, they killed only the body, unleashing the very idea of absolute power.

A new, even more brutal era of civil wars began, in the crucible of which the last remnants of Republican illusions were finally destroyed. Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian—a man of unremarkable appearance but unyielding will and cold political calculation—joined forces with Mark Antony to defeat the conspirators’ armies.

Later, casting aside his former ally, Octavian turned all Roman propaganda against Antony and his lover, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, portraying them as Eastern despots threatening the very existence of Rome. Octavian’s victory in the naval Battle of Actium in 31 BCE made him the undisputed master of the Roman world.

But his true genius revealed itself not on the battlefield, but in the realm of political mythmaking. In 27 BCE, he staged a brilliant spectacle, formally “restoring the Republic” and relinquishing extraordinary powers. In return, the grateful Senate awarded him the honorary title Augustus (“Exalted by the gods”) and, in effect, legitimized his sole rule under the guise of republican forms.

He was not a king, but a princeps—first among equals, supreme commander (imperator), and father of the fatherland. Thus, under the mask of tradition, the Roman Empire was born. His reign, marked by the end of civil wars, extensive building projects, and strengthened borders, went down in history as the beginning of the Pax Romana—two centuries of peace, order, and prosperity made possible only after the Republic, having exhausted its potential, gave way to the new imperial system.

Rome as a Superpower: Influence, Innovation & Administration

By the 2nd century CE, during the reign of emperors from the Antonine dynasty, such as Trajan, the Roman Empire had reached its zenith. Its borders stretched from the misty marshes of Britain in the north to the scorching sands of Arabia in the south, from the Strait of Gibraltar in the west to the fertile valleys of Mesopotamia in the east. The Mediterranean Sea, which the Romans rightly called Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”), had become an internal lake of the empire—a main transportation artery connecting its vast territories.

Governing this colossal, unprecedented expanse required not military valor, but administrative genius. The empire functioned as a complex organism, composed of provinces administered by governors appointed from Rome, alongside buffer client states whose rulers were mere puppets in the hands of the emperor. This flexible system allowed the central authority to efficiently collect taxes, maintain order, and quell pockets of unrest without overextending its limited military resources.

But the true miracle of Rome lay not in its conquests, but in its ability to civilize the lands it conquered. The imperial machine launched an unprecedented program of urbanization and construction. Legions of engineers and laborers built the famous Roman roads—straight, stone-paved, and unmatched in the ancient world. These arteries not only allowed for rapid troop movements but also invigorated trade, linking distant corners of the empire into a unified economic and cultural space.

Magnificent aqueducts, true masterpieces of engineering, carried fresh water into the cities, supplying baths, fountains, and the homes of the elite. Amphitheaters, forums, and basilicas rose everywhere—symbols of Roman lifestyle and power, designed to demonstrate to local peoples the clear superiority of the conquerors’ civilization.

Yet Rome’s greatest legacy, which shaped the future course of European history, was its legal system. Roman law, evolving from the Twelve Tables to the complex codes of the late empire, established revolutionary principles: the presumption of innocence, the concept of a fair trial, the distinction between private and public law, and the idea that law is not the whim of a ruler, but the fundamental foundation of society.

Alongside this, civil rights were expanding. In 212 CE, Emperor Caracalla issued an edict granting Roman citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire. Motivated by fiscal interests, this measure had enormous consequences: a Gaul, a Syrian, or an Egyptian could now rightfully declare, Civis Romanus sum—“I am a Roman citizen.” This sense of shared belonging to a great empire, reinforced by common laws, infrastructure, and culture, became the cement holding this vast world together for centuries.

It was precisely this ability not merely to conquer, but to integrate, assimilate, and impose organized order—turning diverse peoples into a unified body—that made Ancient Rome the first true superpower in history, whose influence is still felt to this day.

Comments