Daily Life in Ancient Rome: Gladiators, Politics, and Entertainment

- Davit Grigoryan

- Jul 28, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

Imagine a city pulsing like the giant heart of an empire. Not just a capital, but an entire world, locked in the stone embrace of seven hills. Ancient Rome was more than just marble temples and triumphal arches rising toward the azure sky. Above all, it was everyday life — boiling in its narrow alleyways and sprawling forums — a life marked by striking contrasts and staggering complexity. The hum of voices in the markets, the smell of fried fish and fresh bread mingling with the acrid stench of open sewers, the clash of swords from a ludus behind a wall, solemn speeches echoing from the rostra in the Forum — all of it blended into the single, restless rhythm of a metropolis that ruled half the known world.

The culture of Ancient Rome was a remarkable fusion: the harsh discipline of legionaries existed side by side with a refined love for poetry and theater; the practicality of engineers coexisted with superstitions verging on fanaticism. But above all, it was about the people. Roman society was sharply divided—like a gladiator’s sword. A senator in a spotless white toga heading to a session in the Curia, surrounded by his clients; a plebeian jostling in line for the annona (the state bread ration); a wealthy freedman building a lavish villa; and a slave barely dragging his feet under the weight of his load—these were lives that rarely intersected. Their experiences in the Roman Empire were vastly different. For one, political intrigues and oyster-filled banquets; for another, grueling labor and a bowl of spelt porridge.

Every day life in Ancient Rome was a true kaleidoscope. It encompassed not only the struggle for survival or power, but also a passionate thirst for spectacle—bloody games in the amphitheater or wild chariot races at the Circus Maximus. Life revolved around public baths, where deals were struck and intrigues were woven, and around household altars, where prayers were offered to the Lares—guardians of the home. As we embark on this journey through the streets of the Eternal City, we’ll touch the lives of its inhabitants—citizens and slaves, the powerful and the powerless, those who shaped the laws of the world, and those who dreamed only of a piece of bread and a sip of freedom. The crowds. The filth. The splendor. The cruelty. The elegance. Welcome to everyday Rome. It will be unforgettable.

Roman Social Classes: From Slaves to Senators

Roman society resembled a giant, precisely constructed pyramid, where every stone knew its place. At the top, basking in the glow of power and wealth, stood the patricians—the descendants of the oldest noble families. Their lives unfolded in luxurious domus houses with atriums and peristyles, where the walls were adorned with frescoes and the floors with mosaics brought from distant provinces. Their day began with receiving clients—crowds of dependent plebeians seeking protection or a small handout (sportula). Then came the Forum: laws, courts, and behind-the-scenes deals in the shadow of the basilicas. In the evening, lavish banquets with Falernian grapes, oysters from Baiae, and philosophical debates. Power was their oxygen, and lineage their impregnable fortress.

The plebeians—free citizens—formed the foundation of this great structure: craftsmen, small traders, and farmers. Their world was noisy and cramped, filled with multi-story insulae rising five or six floors high, where fires and collapses were frequent occurrences. Mornings meant work in a shop or workshop on a bustling street, a daily struggle for survival. Access to politics? In theory—yes, through the people's assemblies (comitia), but real influence remained elusive. Their true power lay in their numbers and their voice—a voice the ruling elite sometimes had to buy with “bread and circuses” (panem et circenses).

Between these worlds lived the freedmen (libertini). Former slaves who had gained their freedom—often through a master’s will or by purchasing it themselves—held limited rights but could accumulate wealth. Many became successful merchants, bankers, or craftsmen. Their status was ambiguous: personal freedom—yes, but with a lifelong obligation to honor and assist their former master, now their patron. Their children, however, were born full Roman citizens. This social "middle layer" was a driving force of the Roman economy, yet the path to political heights remained nearly closed to them.

And finally, the base of the pyramid, bearing its full weight—the slaves. Their numbers were immense. Prisoners of war, those born into bondage, or sold into slavery for debt. The lives of Roman slaves ranged from sheer horror to relative stability. A city slave in a wealthy household might serve as an educated steward (vilicus), a teacher, or a physician, and have a chance at freedom. But the fate of a slave in the quarries, on galleys, or in a gladiator school (ludus) was little better than death: exhausting labor, brutal punishments, and short lives. They were not seen as people, but as “speaking tools” (instrumentum vocale), entirely at the mercy of their master’s will. Their labor fed the cities, built the aqueducts, and clothed the legions.

This ancient Roman class system was rigid, but not entirely immobile. Luck, talent, or the favor of a patron could nudge a person upward. Yet the gulf between the marble mansions of the Palatine and the mud-brick hovels of the Subura—or the chains of a slave—remained the defining feature of everyday life for Roman citizens. Rights, duties, food, clothing, entertainment—everything was determined by the rung on which you were born.

Gladiators and the Arena: Fame and Survival

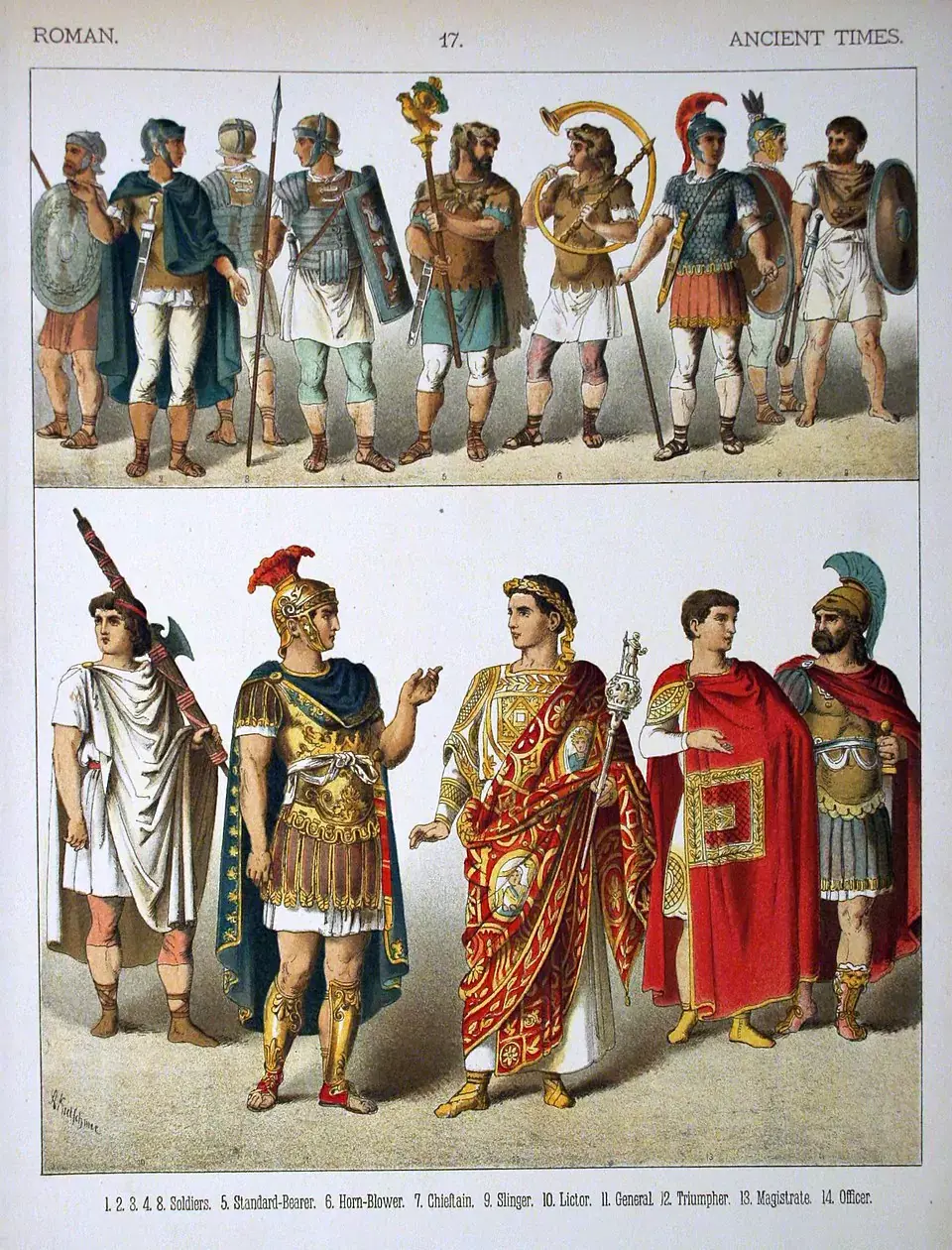

Contrary to popular belief, a gladiator was rarely a doomed slave. In this ancient Roman spectacle industry, a harsh hierarchy ruled. Yes, the core was made up of slaves, prisoners of war, or criminals sentenced ad ludum—“to the school.” Their lives hung by a thread. But alongside them fought volunteers (auctorati)—free citizens, even noble youths, blinded by fame and fortune. One successful fight could earn them more than a legionary made in a year! There were also professional prisoners of war, like the fierce Thracians or Gauls, whose skill was valued like gold.

Their forge was the ludus—the gladiator school, more like a barracks-prison. Iron discipline, meager food (to prevent gaining fat), grueling training with wooden swords (rudis) and shields under the shouts of the lanista—the school’s owner and a former gladiator. Here, they didn’t just shape fighters but specialists. The heavily armored murmillo with his Gallic helmet and gladius sword. The agile retiarius, nearly naked, is wielding a net and a trident. The fearsome secutor, chasing the retiarius. The essedarius, battling from a chariot. Each had its own tactics and deadly techniques. Training was crippling, escapes nearly impossible, and punishments severe. But surviving on the arena’s sand was possible only by enduring the hell of the ludus.

The heart of the bloody spectacle was the amphitheaters. The greatest among them—the Colosseum—is a stone marvel that could hold up to 50,000 spectators! Mornings on the arena floor didn’t start with gladiators but with venationes—the hunting and killing of wild beasts: lions, bears, exotic giraffes, or elephants, slain by hunter-beasts called bestiarii. Then came the executions of criminals, often staged as mythological scenes (being torn apart by beasts symbolized the death of Dionysus). Only after midday, amid the roar of the crowd, did the main stars—the gladiators—enter the arena.

The fight was not a chaotic slaughter but a strictly regulated duel—almost a dance of death. Music played, and judges enforced the rules. The audience—from senators to the lowest plebeians—cheered passionately, placing bets. A wounded fighter could drop his weapon and raise a finger to beg for mercy (missio). Then the crowd decided. A fist with the thumb pointed down (pollice verso) meant "Finish him!" An open palm meant "Spare his life!" Life hung not only on the tip of a sword but also on the crowd’s whim, hungry for spectacle.

The cultural significance of the games was immense. They were a tool of politics—an emperor or an aedile who organized the games bought the love of the plebeians. They also reflected Roman values: discipline (the gladiators’ battle order), courage (virtus), contempt for death, and control over fate (the gesture of the emperor or the crowd). The arena was a microcosm of Rome—brutal, hierarchical, where fame was fleeting, and life’s value measured by the spectacle of death. A gladiator who triumphed and received the wooden sword (rudis), a symbol of freedom, became a legend. But such cases were rare. For most, the arena was only a path to oblivion, strewn with sand, blood, and... the frenzied applause of the Eternal City.

Roman Politics and Public Life: Forums, Senators, and Emperors

Imagine a noise rivaled only by the thunder of chariots at the Circus Maximus. This was the beating pulse of Roman power—the Roman Forum. A narrow valley nestled between hills, crowded with temples, basilicas, and statues, it was the true center of everyday political life. From dawn, activity surged: senators in pristine white togas edged with purple (toga praetexta) marched to the Curia Julia for Senate sessions, accompanied by crowds of clients. Lawyers delivered speeches from the tribunals (rostra), adorned with the prows of captured ships. Money changers jingled coins at the tabernae. Vestal priests, draped in white veils, carried sacred objects into the Temple of Vesta. The air buzzed with gossip, business deals, and political curses. The Forum was more than a square—it was a vast theater where the drama of ancient Roman government unfolded.

The Senate (Senatus)—the council of elders—was formally the heart of the Republic. It's 600 members, all former magistrates, possessed auctoritas—unquestioned authority. They debated laws, foreign policy, finances, and declared war or peace. Sessions in the marble Curia were strictly regulated, presided over by a consul or another senior magistrate. Speeches were delivered in order of seniority. It seemed that the fate of the empire was decided here. But the reality was more complex. As the empire grew and autocratic power strengthened—especially during the Principate era when Octavian Augustus became the first emperor—the Senate’s power became largely ceremonial. The emperor (Princeps) formally “consulted” the Senate, but his will was law. Senators turned into a courtly aristocracy, where intrigue and flattery mattered more than republican principles. A fall from favor or an imperial order to commit suicide could end even the most noble patrician’s career.

But Roman politics was not limited to the Senate. Formally, power belonged to the people (Senatus Populusque Romanus—SPQR). The popular assemblies (comitia)—the Curiate, Centuriate, and Tribal assemblies—elected magistrates and voted on laws. A Roman’s career (cursus honorum) began as a quaestor (finance), then aedile (city administration), praetor (judge), and culminated as consul (the highest military and civil authority, two elected annually). Elections were fierce, often accompanied by voter bribery (ambitus) and street clashes between supporters. Magistrates, vested with authority (imperium), administered justice, commanded legions, and sponsored games at their own expense to gain popularity—a form of populism.

Public life for a Roman citizen was unimaginable without politics, even for a plebeian. Participating in assemblies (though their influence was limited), supporting one’s patron at the Forum, discussing the news at the barber’s or in the baths—all of this was part of their identity. Famous public speeches, like Cicero’s orations against Catiline or Caesar’s eulogy over the body of his wife Cornelia, drew crowds and could shift the political climate. The art of oratory (rhetorica) was an essential skill for anyone aspiring to influence.

By the 1st century AD, however, republican institutions had become little more than a façade. Real power was concentrated in the hands of the emperor and his bureaucratic apparatus. The Senate struggled to retain its fading influence, and magistracies had turned into honorary steps in the career of a senator’s son. The Forum remained a symbol, but decisions were increasingly made in the imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill. Politics shifted from a matter of civic duty to a courtly game, where survival depended on cunning or pleasing the emperor. Yet the noise of the Forum—where once the fate of the world was decided—remained the constant soundtrack of everyday life in Rome, a reminder of the republican past buried beneath the weight of imperial grandeur.

Entertainment and Leisure: Baths, Theaters, and Chariot Races

If politics was the business of the day, then leisure for a Roman—especially after midday—became a true cult. Here reigned an astonishing democracy of spectacle: from the emperor to the poorest pauper, all thirsted for relaxation and entertainment. The center of this social life was the public baths—the thermae. These were not just places to wash but grand cultural and recreational complexes. Imagine marble halls, sparkling pools of varying temperatures (frigidarium—cold, tepidarium—warm, caldarium—hot), rooms for massage and exercise (palaestra), libraries, gardens, shops, and even snack bars. Whether modest neighborhood baths or the lavish Baths of Trajan or Caracalla, Romans came not only to cleanse themselves. Here, business connections were made, gossip spread, philosophical debates took place, deals were struck, and poets or musicians performed. The steam dissolved, if only for a time, the rigid boundaries of social classes. A slave anointing his master with oil, a plebeian in the tepidarium, and a senator in the caldarium—all were united by the ritual of cleansing and relaxation. The thermae were a microcosm of Rome—noisy, crowded, full of life and intrigue.

But the true favorite of the masses was not the baths—it was the chariot races! The Circus Maximus—a gigantic elongated arena at the foot of the Palatine Hill, holding up to 250,000 spectators—became a boiling cauldron of passion during major festivals. The four horse factions (factiones)—the Reds (Russata), Whites (Albata), Greens (Prasina), and Blues (Veneta)—represented not just teams but entire religions for their fans. The charioteers, often slaves or freedmen, became superstars, their names echoing throughout the city. The risk was deadly: lightweight chariots (quadrigae—drawn by four horses) hurtled at breakneck speed into dangerous turns, with collisions and crashes frequent. Seven laps flew by under the deafening roar of the crowd, who placed bets and cheered hoarsely. Victory brought the charioteer enormous wealth and incredible fame, while their faction gained political influence (emperors often patronized specific colors—for example, Nero favored the Greens). The chariot races were pure adrenaline, uniting Rome in a single passionate surge.

The theater in Rome, inherited from the Greeks, had its distinct character. Majestic stone structures like the Theater of Marcellus could hold thousands. But high tragedy or even the comedies of Plautus and Terence were gradually pushed aside by more accessible and coarse entertainments: mimes (short, often bawdy everyday scenes with improvisation) and pantomimes (solo dance performances on mythological themes accompanied by music and chorus). Audiences loved special effects, stage fights, and blatant innuendos. Music followed Romans everywhere: at banquets (symposia), in theaters, at triumphs, and even at work. Flutes, lyres, and citharas rang out both in palaces and taverns.

Leisure in Ancient Rome was diverse: from intellectual conversations in a patrician’s atrium and playing dice (tali) or board games in a tavern, to attending gladiatorial fights (which we have already discussed) or taking simple strolls in the porticoes. But it was the mass spectacles—the chariot races at the Circus, the battles in the Colosseum, the grand performances in theaters and stadiums (naumachiae—naval battles staged in flooded arenas!)—that acted as the cement holding together the empire’s diverse population. “Bread and circuses!” (Panem et circenses!)—This slogan was not just a demand from the crowd but a formula for maintaining power. By giving the people adrenaline, blood, speed, and the steam of the baths, Rome’s elite bought their loyalty, turning entertainment into a powerful tool of social control and unity in a giant, ever-boiling city. Life pulsed not only in the Forum but also in these theaters of life, where everyone—from slave to emperor—sought their piece of joy, escape, or simply a thrill amid sand, steam, and the madness of speed.

Legacy of Ancient Rome

Centuries after the roar of the crowd in the Colosseum and the pounding hooves in the Circus Maximus have fallen silent, the everyday life of Ancient Rome continues to captivate our imagination. Why? Because in this vast historical experiment, we don’t just see artifacts behind museum glass, but a strikingly familiar, vibrant human society in all its contradictory complexity. The Romans gave the world not only aqueducts and roads but an invaluable cultural blueprint whose influence still permeates our civilization today.

Rome’s legacy is, above all, a legacy of contrasts. It lives in the paradoxical coexistence of the sublime and the brutal: the sophistication of Roman law and Stoic philosophy—and the bloody thrill of gladiatorial games. The refinement of Ovid’s and Catullus’s poetry—and the crude pragmatism of “bread and circuses.” The brilliant engineering of baths and forums—and monstrous inequality, where a slave’s life was valued less than that of a good mule. This balance between brutality and refinement is the key to understanding the Roman spirit. They created a system where public baths were centers of social life (the prototype of modern clubs and spa complexes!), and political struggle in the Forum—with its speeches, intrigues, and populism—strikingly resembles the mechanisms of modern democracy (and its crises). The idea of citizenship and duties to the state (res publica) is Rome’s fundamental contribution to Western culture.

The Roman way of life echoes in the most unexpected places. Our modern stadiums, filled with cheering fans, are direct descendants of the Colosseum and Circus Maximus, where passions ran just as high. Contemporary parliaments have inherited the structure and rhetoric of the Roman Senate. Latin roots permeate legal terminology and scientific vocabulary. Even our penchant for public spaces—shopping malls, plazas—traces back to Roman forums and porticoes. And the principle of Panem et circenses (“Bread and circuses!”) remains a universal formula for managing the masses, as relevant today in the age of digital entertainment and media spectacles as it was in ancient Rome.

Ancient Rome in history is not a frozen museum exhibit. It is a living laboratory of humanity, where models of statehood, social organization, urbanism, leisure, and control were tested on a grand scale. By studying their daily life—from the triumphs of emperors to the porridge in a plebeian’s hut, from the bloody sand of the arena to the cool marble of the baths—we gain a deeper understanding not only of them but also of ourselves. We see how fundamental human passions—thirst for power, recognition, entertainment, and security—took shape within concrete historical circumstances.

Roman culture today is not just ruins. It is a living tradition woven into the fabric of our civilization. It reminds us of the power of engineering genius and the dangers of unchecked authority, of the importance of law and the dark side of mass spectacles, of the value of the common good and the destructiveness of social divides. Rome fell. But its shadow, its genius, and its lessons remain long-lasting. They call us not merely to admire the marble of the ruins but to look closely, seeking in the reflection of the Eternal City the features of our own equally complex and contradictory world. Embark on this journey—and you will hear the whisper of Rome not only in ancient texts but also in laws, architecture, and the deepest impulses of our collective life. It is closer than it seems.

Comments