The Start of World War I: From Sarajevo to a Global Fire

- Davit Grigoryan

- Jun 16, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 5, 2025

How did the Sarajevo assassination lead to a global disaster? An analysis of the start of World War I: from Gavrilo Princip’s shot to the fatal decisions of July 1914. Deeper causes—nationalism, alliances, militarism—the July Crisis, and the domino effect. Why did a regional conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia turn into a world war? Read a detailed breakdown.

Europe Before World War I: A Tense Balance

To imagine Europe in the summer of 1914 is to see a continent standing on the edge of a cliff. It seemed that the era of relative peace after the Napoleonic wars and the small 19th-century conflicts had created an illusion of stability. But beneath this calm surface, dangerous currents were stirring, ready to break the fragile order.

The main force behind the tension was the political alliances that wrapped the continent in a steel web. At its center stood the Triple Alliance—Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (though the latter was a “reserve ally” whose loyalty was in doubt). Opposing them was the growing Entente—a union of France and Russia, to which Britain was increasingly joining. These blocs made each member feel safe within, but at the same time, they raised the stakes: a conflict between any two nations from opposing sides would inevitably draw in all the rest. Europe was turning into a giant powder keg.

Nationalism, the powerful spirit of the time, was adding fuel to the fire. In the multiethnic empires—Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia—oppressed peoples (like the Slavs in the Balkans, Poles, Finns, and others) were loudly demanding independence or at least autonomy. Their hopes were often encouraged by neighboring countries that saw it as a way to weaken their rivals. At the same time, strong nation-states—especially the young and ambitious Germany—were fighting for their “place in the sun,” clashing with the interests of older colonial powers like Britain and France. Imperial ambitions and the race for colonies, resources, and markets created constant points of tension around the world.

Militarism was closely tied to all of this. Armies and navies were no longer just for defense—they became symbols of national pride and power. Military leaders had great influence at royal courts and in governments. Across Europe, an arms race was in full swing, especially between Britain and Germany at sea. Armies were growing rapidly, and military spending was taking up a huge part of national budgets.

Even more worrying was that the general staffs were creating detailed, rigid war and mobilization plans. The most famous was Germany’s Schlieffen Plan. It called for a quick defeat of France by marching through neutral Belgium, before slow-moving Russia could fully prepare for war.

The paradox was clear: the more countries prepared for war, the harder it became to avoid. These war plans were like complex clockwork mechanisms—once set in motion, they couldn’t be stopped. Even a small delay could cause disaster. In a way, all of Europe was living on the schedule of a future war, without fully realizing it. All that was left was a spark to ignite the fire that would burn the old world to the ground.

The Spark: Assassination in Sarajevo

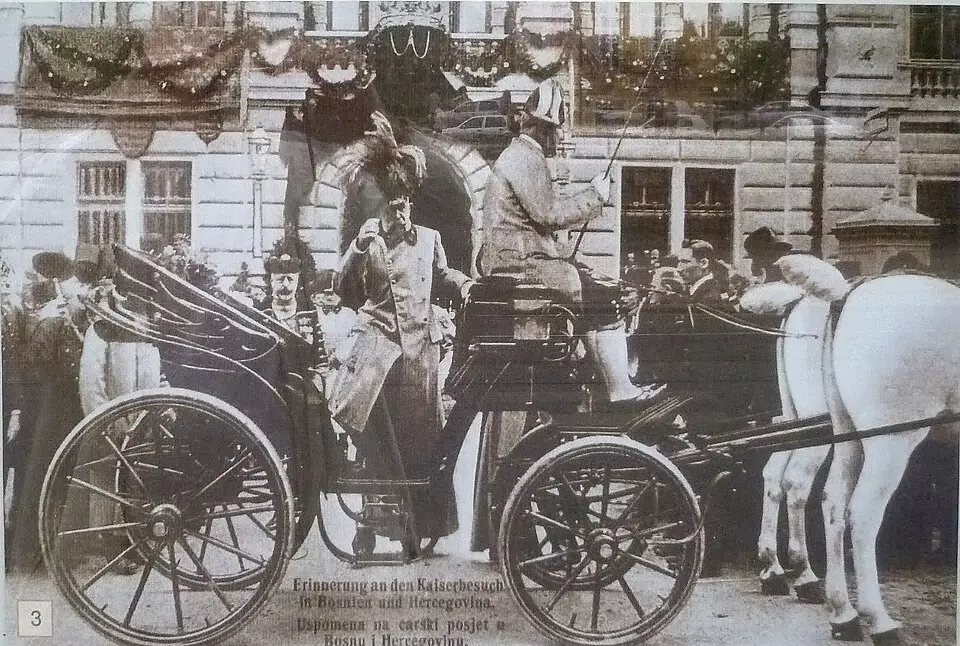

The summer of 1914 was unusually hot. On Sunday, June 28, the capital of Austria-Hungary’s Bosnian province, Sarajevo, was unusually lively. The city was preparing for the visit of the heir to the imperial throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand. His visit wasn’t just a formal event—it was a challenge. Bosnia, annexed by Austria-Hungary only in 1908, was a powder keg of South Slavic nationalism. The Archduke’s trip to the empire’s most tense region—on the very day of Serbian national mourning (Vidovdan, the anniversary of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo)—was seen by many Serbs as an insult and a provocation.

Franz Ferdinand himself was a complex figure. Strict and conservative in politics, he still had plans to reform the patchwork empire into a federation that would give more rights to the Slavs. These ideas frightened the Hungarian elite and... didn’t appeal to radical Serbian nationalists either, who dreamed of a Greater Serbia uniting all South Slavs under Belgrade. It was from this circle that members of the secret group "Black Hand" ("Unification or Death") emerged. They decided to kill the Archduke as a symbol of Austrian oppression.

The morning of the visit began with a troubling sign: the first bomb, thrown by Nedeljko Čabrinović, only slightly damaged the Archduke’s car. It seemed the danger had passed. But Gavrilo Princip, a nineteen-year-old Bosnian Serb with tuberculosis and driven by idealistic fanaticism, did not give up. A twist of fate—a wrong turn by the driver, the car stopping right in front of Princip, and the guards caught off guard—led to tragedy. Two point-blank shots ended the lives of Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie. Princip tried to poison himself but failed and was captured.

The news of the assassination spread across Europe like thunder on a clear day. In Vienna, it was seen as an act of terrorism inspired by Serbia. Although there was no direct proof of official Belgrade’s involvement (Serbian authorities knew about the plot but either couldn’t or wouldn’t stop it), Austria-Hungary was sure: the time had come to end the Serbian threat once and for all. The spark fell on the dry grass of decades of built-up conflicts. What seemed like a regional incident in the distant Balkans became the trigger for a machine no one could stop. Diplomatic notes flew to all capitals, and the clock counting down to disaster ticked louder.

The July Crisis: From Murder to Mobilization

What followed the Sarajevo shots looked less like diplomacy and more like a dangerous game of blind man’s bluff on the edge of a cliff. The July Crisis began—a month of tense unrest, desperate telegrams, and deadly misunderstandings that pushed Europe into war. It seemed the great powers still had a chance to cool Vienna’s anger... but no one truly wanted to take it.

Austria-Hungary, shaken by the heir’s murder, wanted not just to punish Serbia but to crush it as the source of the Slavic threat. The key was an ultimatum given to Belgrade on July 23. Its demands were impossible to meet, especially the demand to allow Austrian investigators into Serbia to find the conspirators. This was a direct attack on Serbia’s sovereignty. Behind Vienna stood Germany, giving its famous "blank check"—a promise of full support that freed Austria-Hungary’s hands. Berlin, confident that Russia would not dare to fight, saw this as a risky but necessary step to strengthen the alliance and isolate Serbia.

Serbia, realizing the deadly danger, replied on July 25 with a surprising concession, accepting almost all the demands. But it could not accept one—the right for the Austrian police to operate on Serbian soil. That was enough for Vienna to break off diplomatic ties. Europe held its breath.

Here began a chain of deadly mistakes and misunderstandings. Russia, seeing itself as the protector of the Slavs, could not allow Serbia to be humiliated. Tsar Nicholas II hesitated between wanting to avoid war and fearing losing face and influence in the Balkans. On July 29, partial mobilization against Austria-Hungary began—a warning signal that Berlin saw as the beginning of the end. The German Schlieffen Plan, this giant clockwork, needed a strike on France before Russia could gather all its forces. Every day of delay was deadly for the plan.

What about England? London was unsure. Sir Edward Grey suggested calling an international conference, but acted weakly, not wanting to tell Berlin that Britain would join the war if Germany attacked France. Berlin wrongly believed Britain would stay out. France, tied to Russia by alliance, promised support to St. Petersburg but still hoped for a miracle. Diplomacy became a shadow play, where the players couldn’t see each other. When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28 and began shelling Belgrade, the last chances collapsed. Russia responded with full mobilization on July 30. Germany saw this as a declaration of war. The clocks, which could not be turned back, started the countdown to a global disaster.

The Domino Effect: Alliances Activate

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914. It seemed like a local conflict in the distant Balkans. But in Europe, tangled in a web of steel alliances, the first falling domino would inevitably knock down the others. The unstoppable domino effect began, where each new war caused the next, and diplomacy was hopelessly falling behind the events.

Russia, loyal to its role as protector of the Slavs and fearing total Austrian dominance in the Balkans, could not stay out. In response to Austria’s aggression, it ordered full mobilization on July 30. For Russia, this was a show of strength and determination. But for Germany, it was a deadly warning. The German General Staff was trapped by the Schlieffen Plan. This plan, carefully designed like a complex machine, demanded speed. It required quickly defeating France before the massive but slow "steamroller" of the Russian army finished mobilizing and attacked Germany’s eastern borders. Every day of delay risked disaster—a war on two fronts, which Germany feared the most. So, Russia’s partial mobilization (against Austria) already caused panic, and full mobilization became a red line for Berlin.

On August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia. This was not just a gesture—it was the start of the Schlieffen Plan in action. According to the plan, the next target was France, Russia’s ally in the Entente. Despite Paris trying to stay neutral or buy time, Germany, wanting to secure its rear before attacking the east, declared war on France on August 3.

But how to strike France quickly? The Schlieffen Plan’s answer was brutally simple: through neutral Belgium. The Germans sincerely (or pretending to) believed it would be a short, almost formal passage. They sent Belgium an ultimatum demanding that it allow their troops to pass, promising compensation. However, small Belgium, whose neutrality was guaranteed by the great powers back in 1839 (the London Treaty), showed unexpected courage. King Albert I and the government rejected the ultimatum. On the morning of August 4, German troops crossed the Belgian border, crushing resistance and causing destruction.

This step proved fatal. For Britain, which had long hesitated and tried to act as a peacemaker, the violation of Belgian neutrality was a casus belli—a formal reason to enter the war. The British government, especially under pressure from public outrage over the "rape of Belgium," could no longer stay out. On the evening of August 4, Britain declared war on Germany. In just seven days after Austria declared war on Serbia, Europe plunged into a continent-wide nightmare. Alliances, long seen as a way to keep peace, became a self-destruction machine. The world collapsed under the thunder of millions of soldiers’ boots marching toward the borders.

Why It Escalated: Underlying Causes

The Sarajevo shot was only a spark. For the fire to engulf the entire world, a mountain of dry kindling, accumulated over decades, was needed. The July Crisis and the domino effect showed how the war began, but the key to understanding why lies in the deep, systemic ailments of early 20th-century European society.

Alliances: A Double-Edged Sword. The alliance system (Triple Alliance vs. the Entente) was created to contain tensions and maintain a balance of power. But in practice, it became a deadly trap. Countries felt overly secure, which encouraged risky moves, like Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia. The mechanisms for peacefully resolving disputes between these blocs were weak. When the crisis hit, alliances triggered automatically, turning a local Austro-Serbian conflict into a full-scale European war. The logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my enemy” prevailed over reason.

Nationalism: Both Poison and Fuel. This powerful spirit of the era had two dangerous sides. Inside empires like Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia, it fueled separatism among oppressed peoples, especially the Slavs in the Balkans, making those regions highly unstable. Serbian nationalism, dreaming of a “Greater Serbia,” directly led to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. Outside the empires, nationalism appeared as chauvinism and a belief in national superiority. France longed for revenge over the 1870 defeat and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. Young, dynamic Germany, feeling deprived of its “place in the sun,” aggressively demanded a redistribution of colonies and influence, frightening its neighbors. Nationalism created a “us versus them” atmosphere where compromise was seen as weakness.

Militarism: The Cult of Power and Fatal Plans. The army became not just a defender but a symbol of national strength and pride. Military leaders held immense influence over politicians, promoting the idea that war was inevitable—and even beneficial for “strengthening” the nation. The arms race, especially the naval competition between Britain and Germany, drained budgets and fueled fear. But the most dangerous were the rigid mobilization plans, particularly Germany’s Schlieffen Plan. These plans were like complex clockwork mechanisms: once set in motion (like Russia’s mobilization), they were nearly impossible to stop without risking disaster. Generals thought in terms of timetables and schedules, not political flexibility. They believed the war would be quick and victorious—a fatal mistake.

Imperialism: The Struggle for World Domination. Vast colonial empires like Britain and France clashed with aspiring powers such as Germany and Italy across the globe—in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The fight for markets, resources, strategic bases, and prestige created constant tension. Germany, late to the “division of the world,” felt disadvantaged, and its ambitions were seen by the old powers as a threat to their global dominance. Imperialism turned local conflicts into potential flashpoints for a world war.

To this volatile mix were added fatal human miscalculations: overconfidence of leaders who believed their enemies “wouldn’t dare,” misunderstandings of others’ intentions (as with Britain), pressure from a public stirred up by chauvinistic press (“war by Christmas!”), and a fatalistic view of war as an inevitable historical event. In the end, when the spark fell, Europe was not just ready for a fire—it was soaked in fuel down to the last beam.

Conclusion: A Global Conflict Ignited

So, how did the shots fired in distant Sarajevo echo as the roar of guns in the fields of France, the mountains of Italy, and even the sands of Mesopotamia? The story of the start of World War I is not a simple chain of events but a deadly mix of long-building tensions and sudden decisions made in blind haste.

Key stages of the fall into the abyss:

The spark: The assassination of Franz Ferdinand by a Serbian nationalist became the excuse that Austro-Hungary, pushed by Germany’s “blank check,” was eager to use to crush Serbia.

Crisis of control: The July Crisis revealed the failure of diplomacy. Austro-Hungary issued an impossible ultimatum. Serbia, despite its concessions, could not fully give in. Russia, seeing a threat to Slavic people and its influence, began mobilization — a move Germany, trapped by its Schlieffen Plan, saw as a casus belli.

Alliance machine: The mobilizations and declarations of war set off a giant mechanism with one program — war. Germany declared war on Russia (August 1) and France (August 3), and to attack France, it violated Belgium’s neutrality (August 4). This was the last straw for Britain, which joined the war that evening. In just one week, a local Balkan conflict spread across all of Europe.

The main tragedy of July 1914 was that none of the key players truly wanted a Europe-wide war. Austria wanted to defeat Serbia, Germany aimed to support its ally and isolate Russia, Russia sought to protect Serbia and keep its prestige, France wanted to honor its alliance, and Britain aimed to defend Belgium and maintain the balance of power. But every action, driven by fear, ambition, alliances, or military plans, dragged everyone deeper into the conflict.

Why did a regional conflict become global?

Systemic nature of the crisis: The deep-rooted causes—nationalism, imperial rivalry, militarism, and the system of rigid alliances—created an environment where any serious crisis risked spiraling out of control. Europe was oversaturated with "fuel."

The inevitability of military plans, especially the Schlieffen Plan. It demanded speed and did not allow for pauses. Mobilization meant war, and any delay meant military catastrophe.

Failure of containment: No one could or wanted to stop the wheel. Germany did not restrain Austria, Russia did not halt mobilization, and Britain did not give Germany a clear warning in time. Diplomacy lost to military logic.

The "vicious circle" effect: Fear of aggression from a neighbor forced preparations for the worst, which in turn increased the neighbor’s fear.

World War I did not start because of a single cause or decision. It was the result of a fatal combination of long-term, systemic illnesses in the European order and a short series of shortsighted, hasty steps taken by leaders who became prisoners of the very alliances, plans, and prejudices they created. The spark in Sarajevo did not fall on empty ground but on a minefield laid by decades of imperial rivalry and national hostility. When the first mines detonated, it was already impossible to stop the chain reaction. The world as it was known ended in August 1914. The price of this "Great Break" proved unimaginably high.

Comments