The Indus Valley Civilization: The Lost Ancient City

- Davit Grigoryan

- Aug 1, 2025

- 9 min read

Imagine this: long before the pyramids of Giza rose above the Nile, long before Babylon became famous for its Hanging Gardens, a remarkable and highly advanced civilization was already thriving on the fertile plains nourished by the great Indus River and its tributaries. We’re talking about the Indus Valley Civilization (also known as the Harappan Civilization) — one of the greatest mysteries of the ancient world, a true "lost ancient civilization of India," whose silent ruins have guarded secrets that have fascinated archaeologists and historians for over a century.

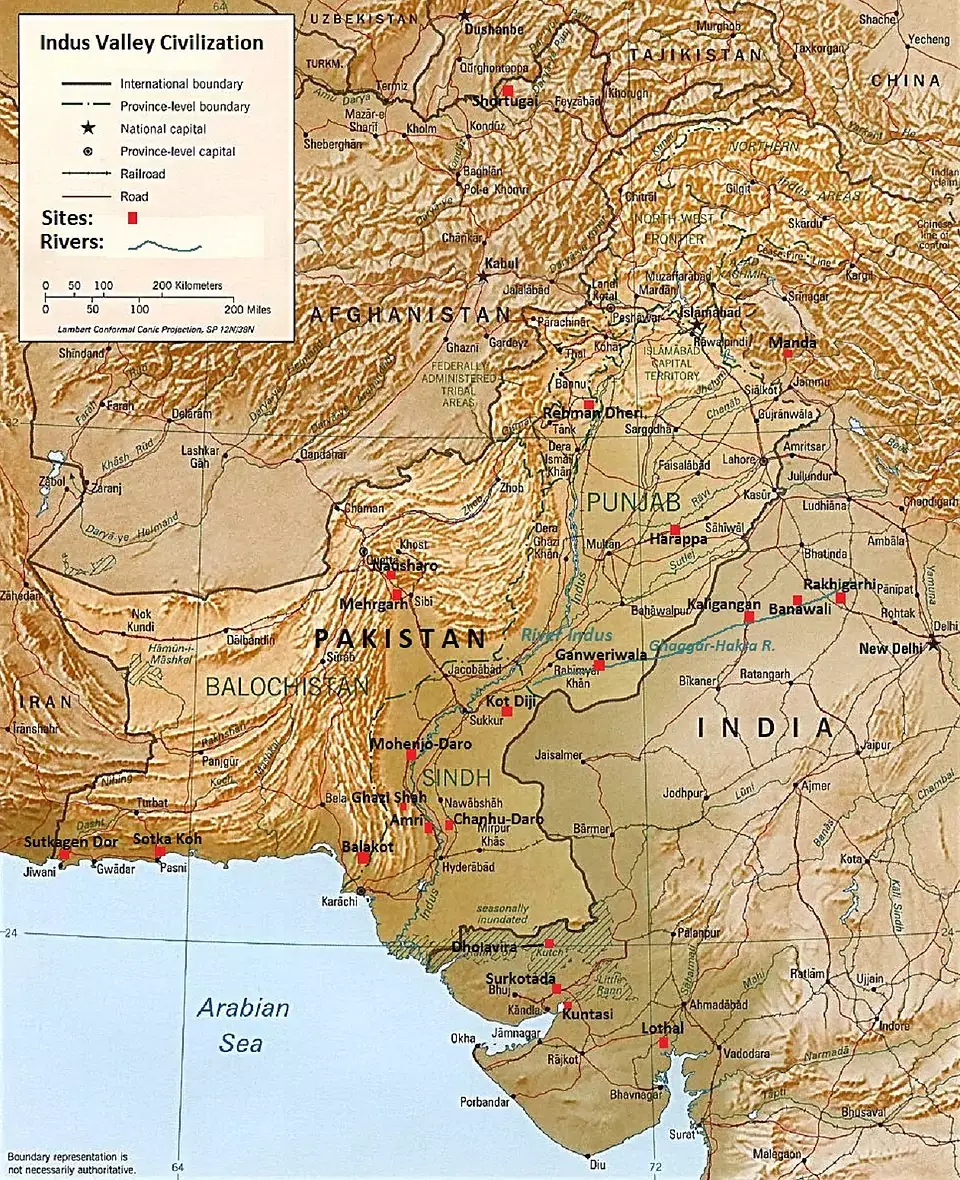

The peak of this culture occurred during the Bronze Age, roughly between 2600 and 1900 BCE. Remarkably, this makes it a contemporary — and in some aspects, even older — than its famous neighbors, Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. It wasn’t just a scattered group of settlements but a vast, well-organized cultural entity that spanned a territory larger than that of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia combined — stretching from the foothills of the Himalayas in the north to the Arabian Sea coast in the south, and from the eastern borders of Iran to the western regions of present-day India.

At the heart of this empire without emperors — a civilization without the famous names of pharaohs or kings that we know — stood its majestic cities. The names Mohenjo-daro (“Mound of the Dead”) and Harappa now sound like magical keys to this forgotten world. It was here, beneath layers of sand and time, that archaeologists in the early 20th century began unearthing evidence of astonishing complexity and order. These cities were not primitive settlements — they impressed with their thoughtful design, vast scale, and technical solutions that seem strikingly “modern” even today.

What makes this civilization so unique and mysterious? Why did it, after reaching such impressive heights, simply... vanish, fading into obscurity for millennia? Was it the absence of grand palaces or pyramids so typical of Egypt? Or perhaps it's a quiet yet incredibly efficient organization? And what happened to its creators? Exploring the Indus Valley Civilization is a journey into the depths of time — an attempt to unravel the mystery of one of the most significant, yet most “silent,” societies of the ancient world. Are you ready to embark on a journey and lift the veil on this lost ancient civilization?

Urban Planning and Architecture in The Indus Valley Civilization

Imagine walking through the streets of Mohenjo-daro or Harappa more than four thousand years ago. What would you see? Not a chaotic maze of mud huts, but a remarkably well-planned city whose architecture and urban design would make you question everything you thought you knew about the “primitive” ancient world. It was a world of order, cleanliness, and engineering ingenuity — astonishingly modern in spirit.

The first thing that catches the eye is the strict grid layout of the streets. Yes, the ancient Indus people thought in rectangles! Broad, straight main avenues intersected at right angles with narrower side streets, forming neat city blocks. This ancient system of urban planning ensured not only efficient movement but also... hygiene. And this is where the truly astonishing part begins.

Beneath these paved streets lay a true engineering marvel — a complex system of drainage and water supply. Every house, even the most modest, was connected to a network of underground sewers, covered with sturdy bricks and equipped with inspection shafts for cleaning. Imagine that: wastewater was systematically directed outside the city, while in other great civilizations of the time, it often flowed openly through the streets. Cleanliness wasn’t just an idea — it was a lived reality.

The pinnacle of this hydraulic and social ingenuity was the “Great Bath” of Mohenjo-daro. This was no ordinary pool — it was a monumental structure built from carefully fitted bricks, sealed with a waterproof layer of bitumen. Surrounded by colonnades and adjoining rooms, it served more than just bathing purposes; it likely played a role in rituals or public gatherings — an ancient prototype of a civic center. Nearby stood the “Citadel,” a fortified upper part of the city, where administrative buildings and massive granaries were likely located — impressive both in scale and in their efficient spatial organization.

The homes, built from standardized fired bricks (yet another sign of advanced technology!), were often two stories high, with inner courtyards, staircases, and even bathrooms. The absence of massive palaces or temples — so characteristic of Egypt or Mesopotamia — suggests a different kind of social structure, possibly a more egalitarian one, where resources were invested not in glorifying a single ruler but in improving the quality of life for all citizens. Their brilliance lay not in monumentality, but in functionality, cleanliness, and an extraordinary sense of order. How did they achieve such a level of organization? That question continues to fascinate scholars today.

Daily Life, Economy, and Trade in the Indus Valley

Behind the strict street grids and brick facades of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, the lives of ordinary people buzzed with activity. What did the inhabitants of this remarkable civilization do? How did they provide for themselves, and what goods did they trade? Daily life in the Indus Valley was deeply connected to fertile land and skilled craftsmanship.

The foundation of the ancient Indian economy was, of course, agriculture. The Indus people were skilled farmers. They cultivated wheat, barley, peas, melons, sesame, and even cotton — one of the earliest in the world! Their fields were irrigated through complex canal systems that diverted water from the Indus River and its tributaries. They also raised animals: zebu (humped cattle), buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, and chickens. And here’s a remarkable fact — they even domesticated elephants! Craftsmanship reached incredible heights. The cities buzzed with workshops of potters, weavers, metallurgists (working with copper, bronze, lead, and tin), and especially jewelers and stone carvers.

Here, their astonishing craftsmanship truly shines. Imagine tiny beads made of carnelian (a red stone), drilled all the way through with an incredibly fine drill — a technology complex even by today’s standards! Or delicate bronze figurines of a dancing girl or a “priest-king.” But perhaps their hallmark was their seals. Usually carved from steatite (soapstone) and then fired for durability, these small square amulets are decorated with images of animals (unicorns, bulls, elephants, tigers) and — most intriguingly — mysterious symbols. This is the famous undeciphered Indus script, one of the civilization’s greatest puzzles. Were these the names of owners, trademarks, or religious symbols? We don’t know yet. But these seals played a key role in trade and the economy.

The Indus people traded actively and over great distances! Their economic ties stretched to Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have found Indus seals, beads, and ivory items in ancient Sumerian cities such as Ur. In the port city of Lothal — another important center of the civilization — traces of massive docks and warehouses have been uncovered. What did they export? Cotton textiles (a rarity for the time!), valuable hardwoods like teak, ivory, precious stones, and intricate jewelry. They imported metals (copper, tin, gold, silver), semi-precious stones (lapis lazuli from what is now Afghanistan), and possibly oils. They even had a standardized system of weights — carefully carved stone cubes (most often made of carnelian or limestone) in precise weight categories (such as ratios of 1:2:4:8, and so on), indicating an incredibly advanced and organized trade network. Their economy was not just sustainable — it was global for its time.

Mysterious Decline: Theories Behind the Fall

By around 1900 BCE, the majestic cities of the Indus Valley, such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, began to empty. By 1300 BCE, the civilization that had lasted nearly a millennium had virtually vanished from the face of the earth. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilization remains one of the most intriguing and hotly debated mysteries of the ancient world. Why did such an advanced society, with its brilliant organization and extensive trade network, simply... disappear? Archaeologists and historians have proposed various hypotheses to explain the collapse, but no definitive answer has been found to this day. It truly is a lost civilization in every sense of the word.

One leading theory links the collapse of Mohenjo-daro and other centers to dramatic climate and environmental changes. Imagine a centuries-long drought. The Indus River, the lifeblood of the civilization, shifts its course or runs shallow. Evidence for this is found in geological layers and paleoclimate data — such as analyses of ancient soils and stalagmites. A lack of water meant disaster for agriculture, the foundation of their economy. Famine, crop failures, and a mass exodus from cities in search of food — a logical chain leading to decline. Some researchers also see signs of massive flooding (especially in Mohenjo-daro), which could have destroyed irrigation systems and poisoned the soil with salt, rendering it infertile. Salt crystals found in the city’s bricks seem to support this “salinity” hypothesis.

For a long time, the invasion theory was popular. Its proponents pointed to human remains found in Mohenjo-daro in unusual positions, as if they had died suddenly (though these were not mass graves of the slain). This was linked to the arrival of warlike nomads — the Aryans, described in the ancient Indian texts of the Rigveda. However, archaeology has found no convincing evidence of widespread destruction from war or fires engulfing all the cities. Nor is there a sudden shift in material culture immediately after the decline of the Indus. Rather, it appears to have been a gradual fading and transformation.

There are other theories as well: the spread of epidemics in overcrowded cities, social upheavals, or internal governance crises triggered by environmental problems, and disruptions to vital trade routes with Mesopotamia. It’s possible that a combination of factors was at play: drought weakened the economy, causing famine and social instability, which made the cities vulnerable to external pressures or disease.

The main challenge in unraveling the mystery of the decline is the absence of written records. The undeciphered Indus script remains silent. We don’t know what the inhabitants themselves thought or felt during the final days of their cities. Archaeologists find only material traces of gradual abandonment: declining construction quality, overcrowded citadels, and deserted neighborhoods. Between the layers of prosperity and the arrival of entirely different cultures lies a “dead layer” — a period about which we know very little. So why did they disappear? For now, we have only hypotheses, and the answer continues to elude us, making the Indus Valley Civilization all the more fascinating and tragic.

Legacy and Rediscovery: Impact on Modern South Asia

For many millennia, the majestic cities of the Indus Valley lay silent, hidden beneath layers of silt and sand, their names erased from human memory. They became the true "lost civilization." But in the mid-19th century, something remarkable happened. While constructing the East India Railway, workers digging ballast for the tracks in what is now Pakistan’s Punjab region came across piles of unusually well-made, ancient bricks. The site was called Harappa. Those bricks were used to build the railway... but the discovery caught the attention of archaeologists. This marked the beginning of the greatest archaeological find of the 20th century — the rediscovery of the Indus Valley Civilization.

At first, the full scale of the discovery was not realized. Systematic excavations at Harappa, and later at Mohenjo-daro in the 1920s under the leadership of researchers such as John Marshall, Rai Bahadur Dayaram Sahni, and Mortimer Wheeler, caused a sensation in the academic world. What revealed itself to their eyes was not primitive settlements, but carefully planned Bronze Age metropolises with sewage systems and public baths! This completely overturned existing ideas about the ancient history of South Asia. Suddenly, it became clear that the roots of Indian and Pakistani culture run much deeper than previously thought — reaching back to an era before the arrival of the Aryans and the composition of the Vedas. This was an indigenous greatness all its own.

The legacy of the Indus Civilization is deep and multifaceted. It is a key element of national identity for both modern India and Pakistan. The ruins of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa (now UNESCO World Heritage sites) are more than just archaeological monuments. They stand as symbols of ancient glory and complexity—a reminder that long before partitions and empires, this land was home to a highly organized, peaceful (judging by the absence of clear evidence of widespread violence), and technologically advanced culture. Its images—such as the famous seals depicting the bull or the “dancing girl”—adorn textbooks, museums (the National Museum in Delhi, the Harappa Museum in Pakistan), and even official state emblems.

But the legacy is not only carved in stone. Some researchers see echoes of Harappan culture in later regional traditions: perhaps in animal and tree worship, in water-related purification rituals reminiscent of the Great Bath, or even in certain elements of urban planning in subsequent cities. Excavations continue to this day—including underwater investigations off the coast of Gujarat, where traces of ports like Dholavira have been discovered—constantly yielding new data and prompting us to rethink the past.

The ancient history of South Asia has found its deepest roots thanks to these excavations. The Indus Valley Civilization ceased to be a myth. It spoke again — through its bricks, seals, and carefully planned streets — after 3,500 years of silence, reminding us of the fragility of even the greatest cultures and the incredible capacity of humanity for organization and creativity in the distant past. Its cities, lost and rediscovered, have forever changed our understanding of the ancient world.

Comments