Most Famous Medieval Queens in History

- Davit Grigoryan

- Jun 23, 2025

- 12 min read

When we talk about the Middle Ages (which lasted about a thousand years from the 5th to the 15th century), we often imagine knights in armor, strong castles, and powerful kings. But the story of this complex and fascinating time wouldn’t be complete without people whose influence often stayed in the shadows but was just as important – the queens. Let’s move away from the simplistic view of them as merely the wives of kings or decorative items at court.

Medieval queens were real, complex individuals whose roles extended far beyond their formal duties. They were rulers — sometimes managing large lands alone when their husbands were away or ruling in the name of their young sons. They were top-level diplomats, whose marriages could bring peace or start wars, and whose talks could stop bloodshed. They were warriors, able to lead the defense of a castle or even inspire an army at a key moment. And, of course, they supported the arts and culture, turning their courts into centers of learning where poetry, music, architecture, and theology could thrive.

Just a shadow of the king? Not at all. Many queens had power, ambition, intelligence, and political will that let them not only influence events but actively shape them. They fought for power, protected the interests of their children and dynasties, managed complex state affairs, and left a strong mark on the history of their countries and all of Europe.

In this article, we’ll bring history to life and get to know the most remarkable and influential queens of the Middle Ages. We’ll travel across the continent — from England and France to Spain and faraway Kievan Rus — to see how these extraordinary women changed the world around them. Ready to meet the legends?

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204)

Imagine a woman who was queen of two powerful kingdoms — France and England — and remained one of the richest and most influential people in Europe for most of her long life. That was Eleanor of Aquitaine — not just a queen consort, but a true political force and cultural trendsetter of the 12th century.

At just 15, Eleanor inherited the vast Duchy of Aquitaine, instantly becoming one of the most sought-after brides in Europe. Her first husband was King Louis VII of France. Their marriage was… stormy. Eleanor had no intention of staying quiet in the background. She joined Louis on the Second Crusade (1147–1149)! Imagine it: a queen in armor (or in luxurious tents — historians disagree), traveling with the army through dangerous lands. Stories spread about her courage (and even rumored romances), and the crusade failed, making the cracks in their marriage even deeper. The annulment of their marriage became a sensation!

But Eleanor didn’t stay single for long. Just a few weeks (!) after the annulment, she married Henry Plantagenet, a young and energetic Duke of Normandy who soon became King Henry II of England. Now she was Queen of England — and her lands in France (Aquitaine) became a major source of conflict between her new husband and her former one!

Their marriage was also full of fire, both personal and political. They had eight children, including future kings Richard the Lionheart and John Lackland. Eventually, Eleanor even supported a rebellion by their sons against their father, and for that, Henry locked her up for nearly 16 years!

But even in captivity, her spirit remained unbroken. Freed by her son Richard, she became his regent while he went on the Third Crusade. She ruled in his place, handled diplomacy, and helped raise the ransom when Richard was captured.

She was also a legendary supporter of troubadours and courtly literature, turning her court in Poitiers into a center of culture and romantic ideals that influenced all of Europe. Eleanor was the embodiment of medieval power, passion, and incredible inner strength.

Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504)

If Eleanor of Aquitaine was a hurricane, then Isabella of Castile was a steel core around which a whole kingdom was built. Her name is closely linked to the birth of modern Spain. But the path to this triumph began with bold defiance.

Though not first in line to inherit Castile, Isabella had an unbreakable will. Against the wishes of her half-brother, the king, she secretly married Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469. This wasn’t a romantic choice but a brilliant political move.

The union of the two most powerful crowns on the Iberian Peninsula — Castile and Aragon — laid the foundation for a united Spain. They ruled as equal partners — the "Los Reyes Católicos" (the Catholic Monarchs) — and this team changed the map of Europe.

Their main shared goal was to complete the Reconquista — the centuries-long fight against the Moorish states in the south. In 1492, after a long and exhausting siege, the Emirate of Granada fell. This victory was not just a military triumph but a powerful symbol: Christian Spain was united under their rule. Isabella was personally present in the military camp, inspiring the troops, not as a warrior with a sword, but as a firm symbol of faith and determination.

But 1492 gave the world more than just Granada. It was Isabella who, after much hesitation and against the advice of many counselors, agreed to fund Christopher Columbus’s risky plan. Her decision, supported by her own money (they say she even pawned her jewels!), opened the New World to Spain — and Europe — starting an empire on which “the sun never set.”

Her deep, sometimes fanatical faith showed in the creation of the infamous Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of Jews (in 1492) and later Muslims. This was the dark side of her rule, casting a shadow over her great achievements in uniting and expanding Spain. Isabella was a complex figure: a builder of an empire and a fierce defender of faith, whose unbreakable will changed the course of history forever.

Matilda of England (1102–1167)

Imagine England in the early 12th century. King Henry I, son of William the Conqueror, loses his only legitimate son in a shipwreck. He faces a tough choice. And he takes a step almost unthinkable for that time: he names his daughter, Matilda, as his heir. Not just a "queen consort," but a full queen of England in her own right. This was a shocking precedent in a world where power was seen as a man's privilege.

Matilda, widow of Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, was proud, smart, and confident in her right to rule. To strengthen her position in Normandy (a key part of the English crown), Henry married her to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. The marriage was difficult, but it gave Matilda an important ally and heirs (including the future Henry II!).

When Henry I died in 1135, a crisis broke out. Some barons, unwilling to obey a woman and breaking their oath to Matilda, placed her cousin Stephen of Blois on the throne. Matilda did not accept this. What followed became known in history as a terrible civil war called "The Anarchy" by people at the time. For twenty years, the country was torn apart by fighting, castles burned, and ordinary people suffered.

Matilda showed herself to be determined and fearless. In 1141, her forces defeated and captured Stephen himself! She entered London, ready for her coronation. But then her pride and harshness let her down. The people of London, angry at her arrogance and new taxes, rebelled and drove her out just before the crowning. This was a turning point.

Although later she was trapped in Oxford (from where she made a legendary escape over the frozen Thames, hiding in a white cloak on the snow!) and then in Winchester, she never fully kept control of the situation. The war reached a deadlock. She was never formally crowned. But Matilda did not give up completely.

Her epic struggle cleared the way. According to the 1153 agreement, Stephen remained king until his death, but her son, Henry Plantagenet, was recognized as the heir. A year after Stephen died in 1154, Henry became king as Henry II.

So, although Matilda never became a crowned queen, she secured the throne for her dynasty, proving that a woman could fight for the highest power. Her defeat was a crack in the once-impenetrable wall of male succession.

Margaret of Anjou (1430–1482)

If you look for a symbol of passion and fierce struggle in the chaos of the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), it is without a doubt Margaret of Anjou. This French princess, married to the weak and mentally ill English king Henry VI of Lancaster, was not just a queen consort. She became the main warrior and leader of the Lancastrian party, fighting to the very end for her husband’s crown and, most importantly, for her son, Edward of Westminster.

Her position was shaky from the start. Her French background made the English distrust her. And when Henry VI finally fell into madness and became unable to rule, Margaret took control of the government herself. But her strict style and push to support Lancastrian favorites, especially the unpopular Dukes of Somerset and Suffolk, made powerful York lords angry. These lords also claimed the throne. This started a bloody civil war.

Margaret did not hide behind castle walls. She was a tireless organizer and leader of the resistance. After the humiliating defeat of the Lancasters at Northampton in 1460 and the capture of Henry VI, it was she who gathered a new army in the north. And it paid off! In December 1460, the Yorkists, led by Richard, Duke of York (father of the future kings Edward IV and Richard III), suffered a crushing defeat at Wakefield. The Duke of York himself died in battle — a fierce victory for Margaret.

But fortune is fickle. The Yorkists, led by the young Edward IV, crushed Margaret’s army at Towton in 1461 — one of the bloodiest battles on English soil. The crown passed to the Yorks. Margaret fled with her son but did not give up. She sought help in France and Scotland, showing incredible determination. Her brief triumph — the temporary restoration of Henry VI to the throne in 1470 — came through an alliance with the Yorkist traitor, the Earl of Warwick, known as the "Kingmaker." But it did not last long.

Her tragic end came in 1471. After the defeat at Tewkesbury, where her only and dearly loved son Edward died, Margaret was captured. Soon after, Henry VI died as well—either from illness or was killed. Margaret, broken by grief, was ransomed by the French king. She spent her last years in poverty and obscurity in her homeland. Her fury and desperate fight became a legend, a symbol of a mother’s devotion and a dynasty’s fierce rage that burned England in the fire of war.

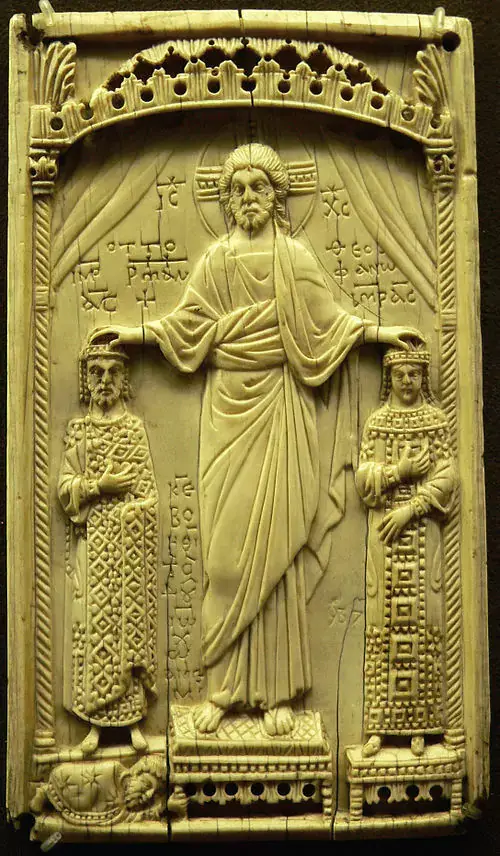

Empress Theophano (c. 955–991)

Imagine a Byzantine princess, raised in the luxury and refined traditions of Constantinople — the "Second Rome." Now imagine her in the harsh lands of the Holy Roman Empire, among fierce German barons. This is Theophano — a woman whose marriage was a diplomatic masterpiece, and whose influence on the young empire was deep and lasting.

Her fate was decided by the great Emperor Otto I. Wanting to strengthen his dynasty’s prestige and gain recognition as equal to the powerful Byzantium, he arranged a marriage for his son and heir, Otto II, with the niece of the Byzantine emperor himself. In 972, the young Theophano arrived in Rome for a grand wedding. She brought with her not only a rich dowry but also a piece of Byzantine grandeur, education, and refined manners.

When Otto II suddenly died in 983, leaving his three-year-old son Otto III as heir, the empire teetered on the brink of chaos. By law and tradition, the regency should have gone to the nearest adult male relative – Duke Henry II of Bavaria, known as "the Quarrelsome." But Theophano, backed by loyal archbishops and her mother-in-law, Empress Adelaide, boldly fought for the regency. She knew Henry aimed to usurp her son’s throne.

Demonstrating remarkable political will and diplomatic skill, Theophano emerged victorious. She became co-regent alongside Adelaide during the minority of Emperor Otto III. Her regency (983–991) was a period of relative stability. She deftly navigated the competing interests of the dukes, defended the empire’s borders, especially in the west against France, and laid the foundations for Otto III’s future reign. Otto dreamed of reviving the Roman Empire in its universal, “Romaios” spirit—a vision undoubtedly nurtured by his Byzantine-educated mother’s ideals.

The true legacy of Theophano, however, was cultural. She became a living bridge between East and West. At her court, Byzantine customs, art, and scholarship flourished. She was a patron of monasteries and scribes, bringing in Greek artisans. Her influence was felt in fashion, with more refined fabrics and jewelry, architecture, court ceremonies, and even education. She instilled in her son a love for classical sciences and the Greek language. Known as the "gift of the Greeks to the Franks," as chroniclers called her, Theophano gently but irrevocably transformed the cultural landscape of the Germanic world, infusing it with a touch of Mediterranean light and sophistication.

Isabella of France (1295–1358)

Isabella, the daughter of the powerful French king Philip IV the Fair and sister to three kings, married English king Edward II in 1308. It seemed like a great match. But this marriage became a curse. Edward II was a weak and unpopular ruler, and most importantly, he openly ignored his young wife, preferring the company of his favorites, especially the hated Piers Gaveston and later Hugh Despenser the Younger.

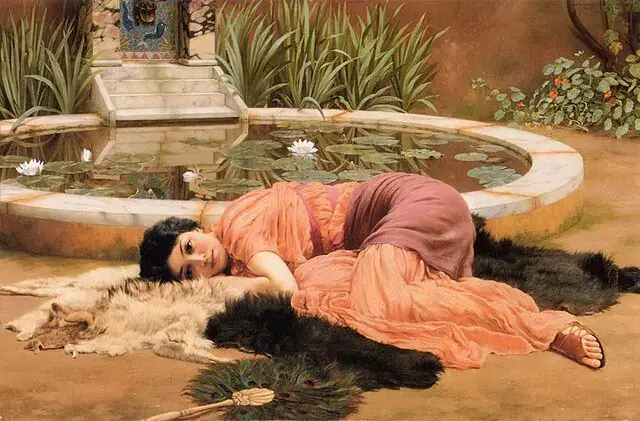

Years of humiliation, political powerlessness (her income was cut, her supporters were removed), and fear for the future of her children (the future Edward III and Joanna) turned Isabella from a submissive queen into a ruthless avenger. Her beauty and intelligence became her weapons. In 1325, on a diplomatic mission to France, she found a powerful ally and lover, Roger Mortimer, a disgraced English baron and enemy of the Despensers.

Together, they gathered a mercenary army. In September 1326, Isabella and Mortimer landed in England. They were welcomed not as enemies, but as liberators! Hatred for the Despensers and Edward II’s weakness was so great that the king’s army simply fell apart. Edward II fled but was captured. The Despensers were seized and executed with unprecedented cruelty (the execution of the elder Despenser became one of the most brutal in English history).

The fate of Edward II himself is shrouded in a dark mystery. Formally, he "abdicated" in January 1327 in favor of his son, the 14-year-old Edward III. But what happened next? A widely spread story—attributed by contemporaries to Isabella and Mortimer—is that he was brutally murdered in Berkeley Castle in September 1327, possibly by the insertion of a heated poker. This savage cruelty forever branded Isabella with the nickname "The She-Wolf of France."

In the early years of young Edward III’s reign, Isabella and Mortimer effectively ruled England, indulging in luxury and abusing their power. But their triumph was short-lived. As Edward III grew older and realized who was truly responsible for his father’s death—or at least who the usurpers were—in October 1330, he carried out a daring coup. Mortimer was captured at Nottingham Castle and executed as a traitor. Isabella was removed from power by her son. She was allowed to retire to her estate, stripped of political influence but allowed to keep some honor. For nearly the last thirty years of her life, the "She-Wolf" lived in honorable yet bitter exile, watching as her son became one of England’s greatest kings. Her fury ultimately turned against her.

Anna Yaroslavna (c. 1024–1075)

Imagine the middle of the 11th century. The Capetian France was not yet a powerful kingdom but rather a collection of semi-independent feudal lands around a small royal domain. King Henry I, widowed and unable to find a bride of proper rank among nearby Christian courts, sent an embassy far away—to the great city of Kiev, to the court of the powerful Prince Yaroslav the Wise. The choice fell on his youngest daughter, Anna. This was a diplomatic sensation!

In 1051, Anna, raised in an environment of learning (her father was famous for his library and laws), arrived in Paris. Her marriage to Henry I was primarily a political alliance, strengthening ties between distant lands. Anna brought with her not only a rich dowry but also the culture, traditions, and connections of Kievan Rus, which was closely linked to Byzantium. She became a living bridge between two worlds—the Slavic East and the Latin West.

Although few documents remain about her direct political role, Anna’s influence was significant. She was crowned as queen consort in Reims. Anna actively supported the Church, founding, among other things, the famous Senlis monastery near Paris, where she later often lived. Her signature in Cyrillic ("Ана Ръина" – "Anna the Queen") appears next to the royal cross on several official charters of her husband, and later her son, Philip I. This is a unique testimony — the earliest known signature of a female ruler of France and a vivid symbol of her origins.

After Henry I’s death in 1060, Anna became regent for the young Philip I, ruling alongside Baldwin V, the Count of Flanders. Her regency was short but important for the kingdom’s stability. Later, her life became mysterious. It is known that she remarried—this time to the powerful Count Raoul de Crépy de Valois, which caused a scandal because he was still officially married. This marriage may have temporarily removed her from court, but toward the end of her life, she returned to her son.

Anna of Kiev is a symbolic figure. She represents the long and deep connections between the Slavic world and Western Europe. Her presence at the French court enriched it culturally, and her son Philip I continued the Capetian dynasty that ruled France for centuries. The memory of the "queen from the land of the Rus" still lives on in France today, especially in Senlis, where a statue of her stands.

Comments