Medieval Castles: More Than Just Fortresses

- Jul 14, 2025

- 9 min read

When we hear the words "medieval castle," we immediately picture huge, strong buildings with high walls, tall towers, and deep moats. And yes, castles in the Middle Ages were mainly built as powerful fortresses to protect their people from enemies. But if we think they were only for war, we miss the true meaning of these amazing structures. They were much more than just stone shields.

Imagine the European landscape from the 10th to the 15th century. Castles rose on hills, at river crossings, and along important roads, not just as defense points. They were powerful symbols of authority and control. Building a castle meant saying, “This land is mine!” For a noble, king, or bishop, a castle was like a business card—a physical sign of their status, wealth, and ambition. The stronger and more impressive the castle, the more powerful and important its owner was. Just look at the imperial palaces of Charlemagne—they were not only homes but also centers of rule over large regions.

But castles were not just homes for the powerful. They became the heart of social and cultural life in their regions. Behind their walls, life was active and full, not just about preparing for constant sieges (though those were always a concern). A castle was an administrative center: it was where justice was carried out, taxes were collected, and the estate was managed. It was also an economic hub: markets, craft villages, and later towns often grew around it. It was a place where court customs, knightly culture, art, and even fashion developed.

The true purpose of castles was to be complex centers of power, governance, economy, and culture—real "nerve centers" of medieval society, with influence that reached far beyond their strong walls. The story of castles is the story of the entire era, frozen in stone.

Architectural Innovations: Building More Than Walls

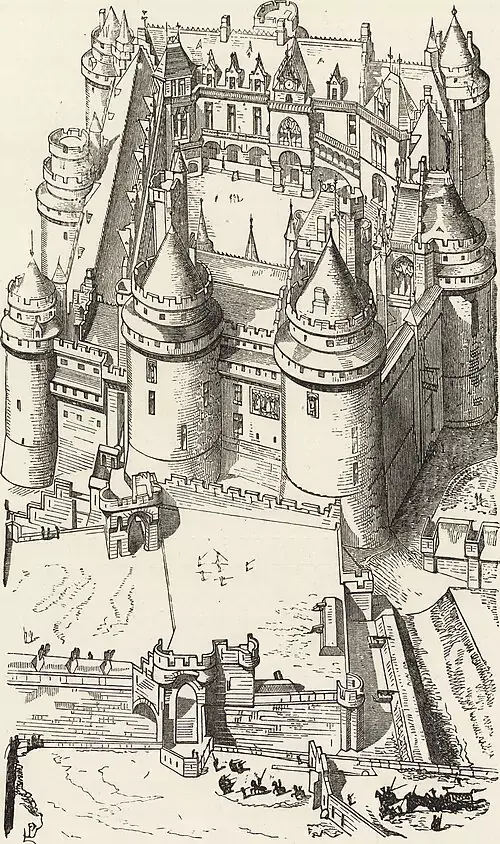

Building a real fortress was not just about piling up tons of stone. Medieval castle architecture was a complex engineering challenge, where every part had to serve two masters: defense and daily life. Castles evolved over the centuries—from simple wooden forts to massive stone giants—and each era left its mark on their design.

Imagine an early castle — a motte and bailey. A wooden tower (called a donjon or keep) stood on a man-made hill (the motte), with a fenced yard (the bailey) below. Simple? Yes. Effective for its time? Absolutely. But fire and time were harsh to wood. Stone took its place.

The key elements of the future stone castle began to emerge in the Norman era: a large rectangular keep became the heart of the fortress, serving both as the lord’s home and the last line of defense. It was surrounded by walls, forming an inner courtyard. But even that wasn’t enough against the growing power of siege weapons and new military tactics.

Castles began to grow layers of defense. Concentric walls appeared—one ring of defense inside another. If an enemy broke through the outer wall, they would enter a deadly trap: a narrow space (called a "zwinger") between the walls, where defenders could shoot from all sides. The famous Krak des Chevaliers in Syria is a perfect example of this system.

Moats, filled with water or simply deep and wide, made it hard to approach or dig under the walls. Drawbridges and strong gatehouses with heavy iron grates (called portcullises) controlled the only entrance.

Round towers, instead of square ones, were better at absorbing hits from battering rams and deflecting cannonballs. Their upper walkways, with battlements and special stone platforms (called machicolations), let defenders fire down at enemies at the base of the walls or pour boiling water or tar through holes in the floor.

But a castle was also a home. Architects didn’t think only about war. Inside the strong walls, life was full and busy. Great Halls were built for feasts and gatherings, more comfortable rooms were made for the lord’s family, with fireplaces and even closets, along with chapels, huge kitchens, storage rooms, stables, and workshops.

Windows stayed narrow for safety, but in living quarters, they began to be decorated with carvings and colored glass. Building techniques improved—from the rough stonework of early Norman keeps to the fine stone cutting seen in Gothic castles like Château Gaillard, built by Richard the Lionheart.

Stone was taken from nearby quarries, and wood from local forests. Building a castle was a massive and expensive task that could take decades. But in the end, the castle became more than just a shield—it was a proud symbol of power carved in stone, and, by the standards of the time, a cozy home for its owner.

Defense Systems: The Science of Protection

The defense of a medieval castle wasn’t just a bunch of random tricks—it was a carefully planned system, a real science of survival. Every stone, every ledge had one goal: to make life as hard as possible for attackers and give defenders the upper hand, even if they were outnumbered. Key defensive features were designed to create deadly traps at every step.

Imagine the attackers. Their path began at the moat, which blocked access to the walls and made tunneling difficult. The drawbridge wasn’t just a road—it was a controlled barrier. In peaceful times, it was lowered, but during danger, it was raised, turning the moat into an impassable obstacle.

Even if the enemy crossed the moat and reached the gates, they faced the portcullis—a heavy iron-reinforced oak grate that could drop in an instant, breaking enemy lines and sealing the passage. And above the unlucky ones trapped in the narrow gateway, there were deadly openings called machicolations—holes in the ceiling or floor of the tower gallery. Through these, defenders poured boiling oil or tar, dropped stones, and threw spears, turning the gate into a deadly “killing zone.”

The walls and towers themselves were covered with arrow slits—narrow vertical openings. Their clever design widened on the inside, giving archers a wide shooting angle while remaining almost untouchable from the outside. The battlements on top of the walls (called merlons) and the walkways along the walls (called wall-walks or fighting galleries) allowed archers and crossbowmen to shoot while taking cover behind them to reload. Corner towers, especially round ones, let defenders fire sideways along the wall, so attackers charging the walls were caught in a deadly crossfire.

But that’s not all. “Murder holes” could be found not only above the gates but also in the ceilings of passages inside the castle. Imagine a narrow corridor leading to the inner courtyard—and suddenly, a shower of stones or boiling water pours down from above. Arrow slits in the basements allowed defenders to shoot enemies right at the base of the walls.

Even the staircases in towers were built as spirals, turning clockwise going up. This put a right-handed attacker (holding a sword in their right hand) at a disadvantage because the wall blocked their swing, while the defender above had full freedom to strike.

Examples of unbreakable fortresses are impressive. Mont-Saint-Michel in France, surrounded by the sea and strong walls, withstood all English sieges during the Hundred Years’ War. Krak des Chevaliers (already mentioned), with its double ring of wall, was considered almost invincible until gunpowder was invented. And the mighty walls and towers of Dover Castle in England, rising above the channel, served for centuries as the “key to the kingdom.”

These castles became masterpieces of medieval military science, where every detail “worked” together to create a complex that attackers had to overcome with great effort and bloodshed. Their battlements, powerful drawbridges, and clever arrow slits still impress today with their smart and deadly design.

Noble Life Within the Walls: Beyond the Battlefield

Imagine this: fierce walls, moats, and towers are just the outer shell. Inside, the medieval castle was full of life, far from constant battles. It was a complex organism—a center of power, management, and everyday life for a whole community. The life of the nobles in these stone giants was like a theater, where dramas of power, luxury, and strict hierarchy played out.

A lord’s morning didn’t start with a sword, but with managing his lands. In his chambers (often in the safest part—the donjon or main tower) gathered his stewards, bailiffs, and elders. Here, courts were held for vassals and peasants, land disputes were settled, and taxes were collected. The castle was the administrative center of the fief.

Nearby, in her sunny rooms (as sunny as narrow windows allowed), the lady of the castle managed an equally complex household: keeping track of food supplies in huge storerooms, overseeing servants, raising children, and supervising tapestry embroidery (which not only decorated cold walls but also helped keep them warm!).

The interior of the castle, in the noble living quarters, aimed for comfort: bright carpets on stone floors, carved furniture, fireplaces, tapestries, and wall drapes—all created spots of warmth and color among the stone.

The day was full of work, meetings, hunting (which was not just fun but also an important source of meat), and teaching children. But the true heart of social life was the Great Hall. In the evenings, this was the main stage of castle society. Long oak tables were filled with food: game, fish, bread, vegetables, cheese, fruits, and of course, rivers of wine and beer.

Feasts and entertainment were not just for fun—they showed the lord’s status and generosity and helped strengthen ties with his vassals. Here, the music of minstrels played, jugglers and acrobats performed, and conversations about politics and knightly deeds took place. Knights showed politeness and respect (courtesy) toward the ladies. Court life shaped manners, fashion, and literary tastes.

But this luxury depended on the work of hundreds of people. Cooks worked magic in huge kitchens with open fires, bakers kneaded dough in special bakeries, stable hands cared for horses in the stables, squires cleaned armor, and servants—from stewards to simple cleaners—moved up and down stairs and halls, keeping this small state running.

Their daily life was tough: cramped and dark rooms in lower floors or annexes, simple food, and hard work from dawn till dusk. The castle followed a strict schedule, with the chapel bell or gong marking times for prayers, meals, and the start and end of work.

Social life in the castle was divided: nobles sat high in the Great Hall, knights and officials were nearby, and servants stayed by the doors or in their quarters. Yet, these walls united everyone under the lord’s protection and power, creating a unique, lively world inside the strong fortress.

Legacy of Medieval Castles: Cultural and Historical Impact

The era of knights and sieges has passed, and cannons wiped stone giants off the battlefield. But medieval castles did not just become silent ruins. Their legacy turned out to be much stronger and deeper than just a memory of military power. These stones, having survived through centuries, became an important part of our cultural and historical DNA.

Above all, castles remain powerful symbols of their era. They are the most visible and tangible proof of the Middle Ages, its feudal system, knightly values, and belief in the strength of stone. Historical castles are like giant books made of stone, whose pages are read in their walls, towers, and layout.

By studying them, we learn not only about military strategy but also about the social structure of society, artistic ideas, the level of technology, and the everyday life of people from the distant past. They are key points on the map of European and Middle Eastern history, places where kingdoms’ fates were decided and legends were born.

The influence of castle architecture on later eras is hard to overestimate. Fortification features—towers, battlements, narrow windows—moved into palace and even manor house designs during the Renaissance, Baroque, and Romantic periods, becoming symbols of aristocracy, tradition, and a romanticized past.

Think of the "castle-like" mansions of the 19th century or the grand, almost fairy-tale Neuschwanstein Castle built by Ludwig of Bavaria—a direct child of the Romantic medieval cult. Even modern urban design shows echoes of castle principles: protected perimeters, dominant features, and a clear hierarchy of spaces.

But perhaps the brightest sign of the castles’ legacy today is tourism. Every year, millions of people flock to castles all over the world. The castles of the Loire Valley, Edinburgh Castle, Prague Castle, the castles of the Rhine, the Moscow Kremlin—the list goes on and on.

What draws us? The desire to touch history, to feel the spirit of the past, to admire the engineering skill and craftsmanship of their builders. The romance of knightly tales, the aura of mystery and legends surrounding ancient walls (what secrets do the Tower’s dungeons hide?), the fantastic silhouette against the sunset—all this makes castles incredibly popular.

They have become pilgrimage sites not only for historians but also for artists, filmmakers, and writers who find inspiration there.

Without a doubt, medieval castles have outlived their original purpose. They no longer protect against enemy armies. But they have protected something even more valuable—memory, imagination, and the connection between times. They remain grand monuments to human genius, ambition, and the desire for safety, beauty, and power.

Their mighty walls and majestic towers still move our hearts, reminding us that true greatness can survive centuries, turning from a fortress into an eternal symbol of history and culture. What makes these ancient stones so captivating? Perhaps the answer lies in their ability to be both powerful witnesses of the past and endless sources of inspiration for the future.

Comments