The Most Famous Kings of the Achaemenid Empire

- Davit Grigoryan

- Jun 30, 2025

- 16 min read

Imagine an empire stretching from the rushing waters of the Nile and the sandy shores of the Indus to the straits of the Aegean Sea and even the edge of the Balkans. Huge like an ocean, colorful like a Persian carpet woven from dozens of people, languages, and beliefs. This isn’t a fantasy, but a reality of the ancient world — the Achaemenid Empire, a giant whose shadow lay over Eurasian history for centuries.

And as often happens, it all began with one man, whose name became a symbol not only of conquest but also of wisdom: Cyrus, later called the Great. It was he who, through both war and diplomacy, united the scattered Persian tribes into the core of a future empire. He then managed to conquer powerful neighbors — Media, Lydia, and finally Babylon — opening the era of Persian rule.

But the Achaemenid Empire is not just a list of conquered lands and tax amounts. It is, above all, the story of its kings — towering, complex figures who left a lasting mark on history. They were not just military leaders, but the architects of an imperial idea, perhaps the first truly global vision of empire.

How did they manage to control such a vast and diverse land? The answer lies in their political genius — a mix of strong military power and, surprisingly for that time, tolerance toward local customs and religions. They built roads that connected the far ends of the empire (the famous Royal Road was an early version of a transcontinental highway), created an efficient administrative system with satraps and organized taxes, and built grand palaces — the crown jewel being Persepolis — which amazed their contemporaries with their size and beauty.

Their decisions — from Cyrus’s humane decrees, recorded on a clay cylinder, to the grand but fateful campaigns of Darius and Xerxes against rebellious Greece — shaped the political, cultural, and military landscape of the ancient world. They set the tone to which all neighboring powers and later rulers had to respond — even Alexander the Great, who, after defeating the Achaemenids, adopted many of their imperial systems.

To understand the ancient East — its rise and fall — without recognizing the role of these Persian “Kings of Kings” is like trying to understand a complex mosaic without seeing its key pieces. Their legacy — in the way they managed vast lands, in the principles of religious tolerance (even if not always fully followed), and in the sheer scale of their ambitions — has lasted through the centuries.

So let’s take a closer look at the most remarkable of these rulers, whose names still echo through time.

Cyrus the Great (c. 600–530 BCE)

If we search history for the figure who truly started the “imperial” idea in its classic form, our eyes inevitably turn to Cyrus. He was not just a successful conqueror, but the true architect of an empire.

Picture this: the mid-6th century BCE. The world is like a patchwork quilt of kingdoms and peoples, often hostile to one another. And from the relatively modest Persian kingdom rises a leader who, in just about two decades, achieves the unimaginable.

His armies, hardened in the struggle against Median rule (around 550 BCE), became an unstoppable force. Media falls. Then comes Lydia — one of the richest lands of its time — ruled by the legendary King Croesus (around 546 BCE), whose treasures are added to the Persian treasury. And finally, the crown jewel of the ancient East — mighty Babylon — surrenders to Cyrus in 539 BCE almost without a fight.

But here’s what truly amazes: Cyrus didn’t just conquer cities and kingdoms — he integrated them. That was his genius and the key difference between him and earlier empires like Assyria, which were known for their brutal cruelty.

Take his entry into Babylon, for example. Instead of bloodshed and destruction, there was respect for local gods and traditions. Cyrus presented himself not as a foreign invader, but as the rightful successor of Babylonian kings — even a “liberator” from the unpopular ruler Nabonidus.

This approach was recorded in one of the most remarkable documents from the ancient world — the Cyrus Cylinder. This clay scroll, discovered by archaeologists in the 19th century, is often called the “first declaration of human rights” (though the term is modern and doesn’t quite fit the time).

The text speaks of allowing displaced peoples to return to their homelands, including the famous release of the Jews from Babylonian captivity and the permission to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem. It also mentions restoring destroyed temples and rejecting a policy of terror.

Ironically, it was this tolerance that became one of Cyrus’s greatest tools of power. Conquered peoples paid taxes and sent soldiers not only out of fear, but because life under Cyrus was often more stable and fair than before.

His death in 530 BCE, during a battle with the nomadic Massagetae on the empire’s eastern frontier, was sudden and tragic. But the state he built — that vast body stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River — proved incredibly strong and lasting.

Cyrus didn’t just draw borders; he laid down the core principles of governance: respect for local elites, flexible administration, and investment in infrastructure (such as the early version of the Royal Road). His image — as a wise, just, and powerful ruler — became legendary even in his lifetime.

The Greeks, who would later become his empire’s enemies, wrote about him with admiration. Even Alexander the Great, who would destroy the Achaemenid Empire centuries later, paid tribute to Cyrus by honoring his tomb.

Cyrus the Great was not just the founder of a dynasty. He was the creator of a model — one that would inspire nearly all great empires of the ancient and medieval world. His legacy lives on in the idea that a vast and diverse world can be ruled not only by the sword, but also with wisdom and respect.

Cambyses II (r. 530–522 BCE)

Imagine the weight of the legacy that fell on Cambyses’ shoulders. To be the son and successor of Cyrus the Great — that was no task for the faint-hearted. And Cambyses, it seems, was strong in spirit. But the star he lit in the sky of the Achaemenid Empire shone with a troubling, blood-red light.

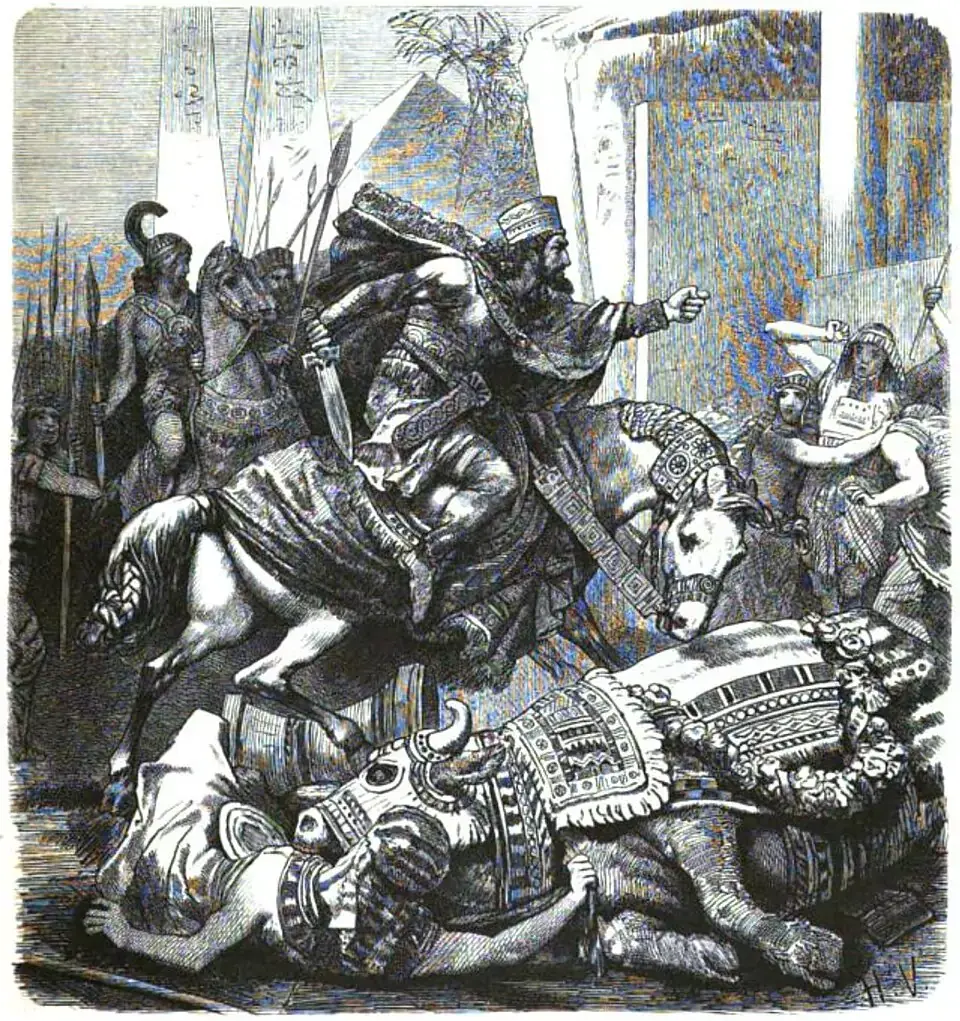

In 530 BCE, he inherited his father's vast empire — a giant realm stretching across continents. And it seems he felt the need to prove himself, to show his own strength and military skill. His eyes turned westward, toward ancient, mysterious, and incredibly wealthy Egypt. The campaign of 525 BCE became a triumph for the Achaemenid military machine. Cambyses didn’t just defeat Pharaoh Psamtik III at Pelusium — he crushed him, showing remarkable strategic skill.

According to some accounts, he used knowledge of local customs to his advantage — for example, sending sacred cats (revered by the Egyptians) ahead of his troops, which confused and demoralized the defenders. He also relied on the betrayal of Greek mercenaries in the pharaoh’s army and the dissatisfaction of parts of the Egyptian nobility.

The fall of Memphis made Cambyses the new pharaoh and founder of Egypt’s 27th Dynasty. He adopted Egyptian royal titles and, at least outwardly, showed respect for the local gods. It seemed that the empire had firmly absorbed the Nile Valley. But here the shadow begins. Cambyses earned the unhappy reputation of the “bad king” in history, mostly written by his enemies, especially the Greek historian Herodotus.

He appears as almost a mad tyrant: a temple desecrator (killing the sacred Apis bull), a murderer of his brother Bardiya (Smerdis), mocking the defeated, and falling into drunkenness. The picture is dark and... highly questionable.

Modern historians and archaeologists increasingly question these stories. An inscription on the statue of Apis clearly states that the sacred bull died a natural death during Cambyses’ reign, was buried with honors, and the pharaoh paid for all the rituals. Egyptian records from that time do not mention any mass persecution of priests.

Yes, Cambyses was a harsh ruler, probably less charming and flexible than Cyrus. His actions in Egypt and his attempt to seize the Siwa Oasis (where, according to legend, an entire army was buried alive in the sands) may have been rougher. He likely did eliminate his brother as a potential rival—a common practice in dynastic struggles of the time.

But was he a mad vandal? Most likely, no. His image in history is a mix of propaganda by the defeated Egyptians, Greek hostility toward the Persians, and black PR by his successor Darius I, who needed to legitimize his rise to power.

The tragic end of Cambyses is shrouded in mystery. In 522 BCE, after receiving news of a rebellion in the very heart of the empire, led, according to the official version, by Darius, by a magician named Gaumata who claimed to be the surviving Bardiya, Cambyses hurriedly began his journey back from Egypt.

He died on the way under strange circumstances—either from an accidental wound caused by his sword (Herodotus says it was a thigh injury, in the same place where he had injured the Apis bull), or from illness, or possibly at the hands of assassins. His death, without an heir, threw the empire into chaos and civil war. After a year of bloody fighting, a new strong ruler emerged—Darius.

Cambyses remains a complex figure in history: a capable general who expanded the empire to its natural western borders, but lacking his father’s charisma and diplomatic skill. His legacy was almost immediately erased and demonized. He stands as a tragic example of how the glory of a conqueror can easily fade in the shadow of a Great Father and under the pen of hostile historians.

Darius I the Great (r. 522–486 BCE)

If Cyrus was the brilliant architect who built the empire’s foundation, then Darius I was its tireless repairman, foreman, and supplier, turning that impressive structure into a well-oiled, functioning machine.

His rise to power began in chaos. After Cambyses’ mysterious death, the empire was shaken by rebellions. A false king (the magician Gaumata, who claimed to be Cyrus’ son Bardiya) took the throne, while uprisings burned on the empire’s edges.

Darius, a young noble from a side branch of the Achaemenid family, carried out a bold coup in 522 BCE with six companions. They killed Gaumata and, in a series of lightning-fast campaigns called the “Year of the Kings,” slowly pieced the crumbling empire back together. His Behistun Inscription, carved into an almost unreachable cliff, is both a triumphant report and a fierce warning: this is what will happen to anyone who dares rebel against the “King of Kings.”

After stabilizing the empire with an iron hand, Darius began a grand reorganization. Imagine a world without the internet or phones, where managing lands from the Indus to the Danube seemed impossible. Darius found solutions.

He divided the empire into satrapies—clearly defined provinces led by satraps (often from the local nobility but monitored closely by the king’s “ears and eyes”—inspectors and secret agents). He introduced a standardized tax system (paid in silver or goods, proportional to the region’s wealth), which was tough on pockets but ensured a steady income. He created a unified currency—the famous gold “daric,” which became a symbol of reliability in the ancient world.

He built (or significantly upgraded) the Royal Road—a true “information highway” stretching 2,700 kilometers, with inns and a courier system that could deliver messages from Sardis to Susa in just days. This was a revolution in governance—the operating system of the world’s first super-empire.

His building projects were no less impressive. He didn’t just finish what was started—he founded Persepolis. This ceremonial complex, built on an artificial terrace, was meant to be a visible symbol of the empire’s power and unity. Its grand apadanas (columned halls) with reliefs showing endless processions of gift-bearers from every corner of the empire served as stone propaganda for the idea of imperial harmony under the Achaemenids. Susa, his administrative capital, was also rebuilt on a scale never seen before.

But Darius’s ambitions went beyond just strengthening and beautifying the empire. He yearned for new conquests. In the east, his armies reached the Indus Valley, adding wealthy lands to the empire. In the west, however, he faced a fateful challenge—Greece. Seeking to punish the Ionian Greeks of Athens and Eretria who had supported a rebellion and to assert control over the Balkans, Darius launched a grand expedition in 490 BCE.

However, the attack on Athens ended in disaster at the Battle of Marathon. Well-trained and motivated Athenian hoplites, using the terrain and smart tactics, decisively defeated the larger but less maneuverable Persian forces. This battle became a symbol of resistance, forever breaking the myth of the Persian army’s invincibility in Europe and planting the seeds for future conflicts.

Darius died in 486 BCE, preparing for a new, even greater campaign against Greece. He left the empire at the height of its power, but with the “Greek problem” unresolved and many critical issues for his son and heir, Xerxes, to face. Darius the Great was a king who proved that holding an empire together was sometimes harder than conquering it—and whose administrative legacy outlasted his military failures.

Xerxes I (r. 486–475 BCE)

Imagine the immense weight of expectations: to be the son of Darius the Great and inherit an empire at the height of its power, yet still bearing the fresh wound — the disgrace of Marathon. Xerxes, ascending the throne in 486 BCE, was destined for either great triumph or catastrophic failure. His choice was a colossal project of the century: to finally settle the “Greek question.” Not merely to punish Athens, but to conquer all of Hellas, turning the Aegean Sea into a Persian lake.

The scale of preparations astonished even contemporaries. A massive pontoon bridge was built across the Hellespont (the Dardanelles) — a bold symbol that no natural force could withstand the will of the “King of Kings.” An armada of hundreds of ships and a land army, which Greek sources exaggerated to millions but more realistically numbered between 100,000 and 200,000, was gathered from every corner of the empire: Immortals, Bactrians, Indians, Egyptians, Phoenicians... This was no mere military campaign but a grand procession of imperial might, designed to intimidate the world.

The opening chords sounded triumphant. In 480 BCE, the Persian avalanche swept through Central Greece after overcoming the Thermopylae pass at a tremendous cost—the legendary sacrifice of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans was just one episode in this drawn-out battle. Athens was captured and burned—the revenge for Marathon was fulfilled. But what went wrong?

The answer lies in Salamis (September 480 BCE). Confident in the strength of his fleet, Xerxes made a fateful decision to attack the Greeks in the narrow straits. Watching the battle from his golden throne on the slopes of Mount Aegaleos, he witnessed how the agile Greek triremes used the confined space to turn Persia's numerical superiority against itself. Phoenician, Egyptian, and Cypriot ships collided, ran aground, and were smashed by ramming attacks. The defeat was crushing. Legend says that Xerxes, in horror, leapt up from his throne three times. Salamis turned the tide of the war. Without naval dominance, supplying the massive Persian army became impossible. The king was forced to retreat to Asia with most of his forces, leaving the seasoned general Mardonius in Greece.

The final verdict on Xerxes’ ambitions was delivered at Plataea in 479 BCE, where the land forces of Mardonius were decisively defeated by the united armies of the Greek city-states. This marked the end of the era of Persian expansion into Hellas.

Xerxes is often portrayed only as a cruel tyrant blinded by pride (sources repeat Herodotus, describing his whipping of the Hellespont and other "madness"). But this is only part of the picture. At home, he was a great builder. It was under him that Persepolis reached its peak: the grand "Hall of a Hundred Columns" (Throne Hall), the Palace of Xerxes, and the monumental Gate of All Nations were built. He completed his father's projects, turning the ceremonial capital into a masterpiece. There is evidence of his attention to religious reforms, possibly linked to strengthening Zoroastrianism and centralizing the cult. He suppressed major rebellions in Babylon and Egypt, though his methods there were harsher than Cyrus’s, which hurt loyalty.

The end of Xerxes was dark and unroyal. In 465 BCE, he fell victim to a palace conspiracy led by the powerful courtier Artabanus and the commander of the royal guard. He was killed in his bedroom. The murder of Xerxes — the son and grandson of the great builders of the empire — in the heart of his palace became a grim symbol of growing internal decay and factional struggles that would eventually destroy the Achaemenid Empire. He left behind a vast empire, but one weakened in prestige after the Greek defeats and overshadowed by the violent death on the throne. Xerxes is a tragic figure of enormous ambitions clashing with unforeseen events, enemy military success, and perhaps the very limits of imperial expansion. His name is linked to defeat, but his contributions to the glory of Persepolis and the empire’s administration are unfairly forgotten in the shadow of the Salamis disaster.

Artaxerxes I to Darius III

The murder of Xerxes in 465 BCE slammed the door shut on the era of great conquests. The throne passed to his son, Artaxerxes I Longhand (reigned 465–424 BCE). His nearly 50-year rule was a story of tireless efforts to keep the empire from falling apart. He was not a builder, but rather a patcher of holes. He had to put down powerful uprisings in Egypt (led by Inaros and Amyrtaeus), supported by the Athenians, and in Bactria. The struggle with Egypt turned into a long war with Athens, during which the Persians skillfully used gold to fuel conflicts among the Greeks themselves (the Peloponnesian War). It ended with the Peace of Callias (around 449 BCE) — formally a compromise, but in reality a sign that Persia gave up its ambitions in the Aegean Sea and recognized the independence of the Greek cities in Asia Minor.

Inside the empire, Artaxerxes tried to keep things in balance by relying on his administration and suppressing separatism, but the spark of imperial drive was gone. His era was one of stabilization through exhaustion — the giant still stood, but the beams were beginning to creak.

The following decades felt like a slow slide downhill. Darius II (reigned 423–404 BCE), the son of Artaxerxes, ruled from Susa, caught up in harem intrigues and power struggles among court factions. His reign is remembered not for achievements, but for the final loss of Egypt (after the revolt led by Amyrtaeus around 404 BCE) — the richest satrapy and the empire’s breadbasket. The power of the satraps grew, while the central government weakened and the treasury ran dry. The empire increasingly resembled a ship whose crew was busy dividing supplies, ignoring the growing leaks.

Artaxerxes II Mnemon (reigned 404–358 BCE) ruled for an unusually long time, but it was a slow-motion sunset. His reign was marked by a parade of rebellious satraps (in Cyprus and Asia Minor), a brutal civil war against his brother Cyrus the Younger (described by Xenophon in the Anabasis), during which the king himself nearly died, and the final confirmation of Egypt’s independence. He continued building projects, trying to imitate his ancestors (palaces in Susa and Ecbatana), but they were only pale shadows of Persepolis. The empire was, in reality, falling apart into provinces ruled by nearly independent dynasts who only nominally acknowledged the authority of the "King of Kings."

Artaxerxes III Ochus (reigned 358–338 BCE) was a harsh and brutal figure. He tried to bring the empire back under control with an iron fist. Through ruthless purges — including the elimination of his own relatives — he restored temporary order at the court. His main goal, which he partly achieved, was to retake Egypt. In 343 BCE, he launched a bloody campaign that succeeded, but it drained the already weakened empire even further. This was the last major effort of Achaemenid power. Soon after, he fell victim to a palace conspiracy and was poisoned by his trusted courtier, the eunuch Bagoas. His successor, Artaxerxes IV Arses, was merely Bagoas’s puppet and was also murdered two years later.

And so, in 336 BCE, Darius III Codomannus stepped onto the stage of history. He was no coward — he had once won the royal hunt — but he was placed on the throne by the same powerful eunuch Bagoas as a convenient figurehead. Darius soon got rid of Bagoas, but then faced a storm named Alexander the Great.

Darius was not weak. He gathered huge armies and tried to stop the Macedonian phalanx at Issus (333 BCE) and again at Gaugamela (331 BCE). But his troops were too diverse and lacked unity. His satraps often followed their ambitions. And Darius himself may have been too cautious. All this worked against him. The defeats were devastating. He fled the battlefield, trying to raise more forces in the east, but was betrayed and killed by his satrap, Bessus, in 330 BCE.

His death marked the official end of the Achaemenid Empire. Alexander captured Persepolis and Susa and became the “King of Asia.” Darius III went down in history not as a villain, but as a tragic figure — the last ruler of a once-great empire, crushed between the hammer of Alexander’s military genius and the anvil of internal decay. The empire, founded by Cyrus the Great and strengthened by Darius I’s system, fell not only to the sword of Alexander, but also because by the 4th century BCE, it had long been rotting from within.

Conclusion

Looking back at the line of “Kings of Kings” of the Achaemenid Empire, it becomes clear that they were more than just rulers — they were the living embodiment of the very idea of Empire, in all its glory and contradictions. From the brilliant visionary Cyrus the Great, who laid the foundations based on strength, rare tolerance for the ancient world, and integration, to the tragic figure of Darius III, desperately trying to hold together the crumbling walls, each king left his own unique, and sometimes bloody, mark.

Their legacy is impossible to overestimate. They created the first true world empire in history, uniting dozens of peoples under one scepter—from the Indus to the Nile. But their greatness was not just in the scale of their conquests. Cyrus gave the world the idea of humane conquest, immortalized on a clay cylinder. Darius I became an unmatched architect of imperial administration: his satrapies, the Royal Road, darics, and well-organized bureaucracy became the gold standard for governing vast lands for centuries to come. They proved that an empire could be ruled not only through fear, but through pragmatic tolerance, respect for local cults and elites, and investment in infrastructure and communication. Even their monumental constructions—especially Persepolis—were more than just palaces; they were stone manifestos of unity in diversity under Achaemenid rule.

But this story also had a fatal flaw. The ambitions of Cambyses—and especially of Darius I and Xerxes—who turned their gaze toward rebellious Hellas, ended in catastrophic defeats (Marathon, Salamis, Plataea). These battles shattered the myth of invincibility and led to massive losses of resources. The successful stabilization under Artaxerxes I only briefly delayed the inevitable. The empire, so brilliantly built and organized, became a victim of internal decay: the growing power of satraps, palace intrigues, bloody coups (like the murders of Xerxes and Artaxerxes III), separatism (such as the loss of Egypt), and chronic financial shortages weakened its once-strong foundations. By the 4th century BCE, the Achaemenid Empire had largely exhausted its strength. It became a “colossus with feet of clay,” ready to collapse under the blow of a bold and talented enemy—Alexander the Great.

So why do we still remember them? The Achaemenids created the blueprint for what it means to be an empire. Their experience—both glorious and painful—became a textbook for all future empire-builders, from Alexander, who adopted their administrative systems, to Rome and later states. Their ideas of religious and cultural tolerance (even if not always perfectly applied) sound strikingly modern. Their massive infrastructure projects remind us of the vital role of communication. Even their downfall is a timeless lesson about the fragility of any power, no matter how great, when it is weakened by internal conflicts and an inability to renew itself.

The shadows of Cyrus, Darius, Xerxes, and other Achaemenid rulers still wander through the halls of history. They remind us of the dizzying heights human ambition and will to organize can reach, of the brilliance of the imperial idea—and the heavy price it demands. Their empire has fallen, but the echo of their rule, their victories, and their mistakes still resonates, woven into the very fabric of our civilization. They were the first to try to embrace the unembraceable—and in that lies both their greatest achievement and their eternal lesson.

Comments